Key Points

- An age-related loss of DNA molecular tags – demethylation – on viral sequences within DNA allows the activation of a harmful sequence – endogenous retrovirus (ERV).

- This age-associated activation of ERV stimulates the production of its proteins – retrovirus-like proteins (RVLPs) – that trigger an immune response and inflammation.

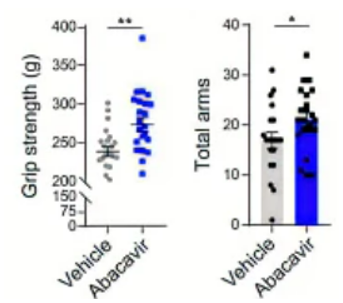

- Antiviral HIV medicine abacavir inhibits ERV gene activity and improves age-related declining grip strength and short-term memory in mice.

The majority of genetics studies analyzing aging determinants have looked at protein-coding genes, but non-coding DNA regions are beginning to garner attention. One so-called non-coding region is the endogenous retrovirus (ERV) – a DNA sequence relic of an ancient viral infection. Comprising ~8% of our genomes, these viral insertions of DNA sequences have evolved with mutations and deletions that render them silent due to their harmful potential. However, whether the most recently-inherited sequences remain inactive has been unclear, and their effects on cells if they’re still active need to be uncovered.

Published in Cell, Qu and colleagues from the Chinese Academy of Sciences show that ERV activation from age-related derepression of its sequence drives human cells to the aged state of senescence, where they evade programmed cell death and emit inflammatory molecules. Once activated, ERVs produce proteins (retrovirus-like proteins [RVLPs]) that trigger an immune response along with inflammation. RVLPs also propagate the immune response and inflammation to neighboring cells. The antiviral HIV drug abacavir that inhibits ERV gene activity improves grip strength and working memory in aged mice. These findings suggest that monitoring ERV protein levels can serve as a way to measure aging, and targeting ERVs with antiviral pharmaceuticals can improve tissue health and function with age.

Viral DNA Sequence Resurrection Drives Aging

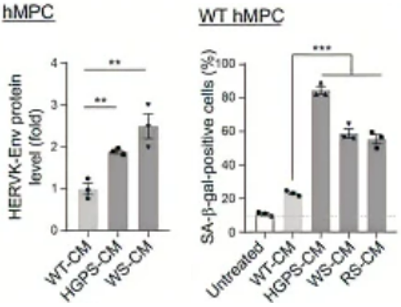

To measure whether ERV derepression induces higher ERV activation and stimulates cellular senescence, Qu and colleagues used human connective tissue stem cells – human mesenchymal progenitor cells (HMPCs). The researchers used cells with premature aging characteristics (Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome and Werner syndrome cell models) and found demethylation for ERV sequences. This genetic ERV derepression was linked to protein markers of senescence in cells along with the presence of proteins that ERV codes for. These findings suggest that an age-related demethylation of ERV sequences activates its proteins’ expression, which is associated with cellular aging and senescence. Moreover, by genetically repressing ERV sequence expression, cells expressed lower levels of senescence marker proteins, supporting that ERV expression with age fuels cellular senescence.

The China-based researchers questioned whether ERV activation could trigger an immune response. They measured proteins associated with the immune response to foreign antigens – the innate immune response – and found that age disorder model immune cells with elevated ERV activation displayed elevated immune proteins. The researchers also found higher levels of the inflammatory protein interleukin-6 in cells with elevated ERV activity. These results support that ERV activation and protein production induces an immune response along with inflammation.

Previous research has suggested that cells can release RVLPs and transmit them to other cells, possibly triggering an immune response and spreading cellular senescence. Along those lines, Qu and colleagues tested whether the culture medium from the aging model cells contained higher levels of RVLPs and whether the same culture medium could induce senescence in healthy cells. Indeed, the researchers found higher RVLP levels in the culture medium from the aging model cells, and when they treated healthy cells with this medium, those cells exhibited higher levels of senescence-associated proteins. These findings suggest that RVLPs from aged and senescing cells can spread to other cells and trigger senescence.

Qu and colleagues wanted to test whether inhibiting RVLP formation from ERVs with the antiviral drug abacavir could functionally ameliorate signs of aging in mice. They treated aged mice with abacavir in their drinking water for six months and found that the drug improved grip strength and short-term memory. These results support that the antiviral drug abacavir can improve signs of age-related physiological decline, likely by inhibiting RVLP buildup and subsequent senescence.

“We discovered a positive feedback loop between endogenous retrovirus activation and aging,” said Qu and colleagues. “Our research provides experimental evidence that the conserved activation of ERVs is a hallmark and driving force of cellular senescence and tissue aging. Our findings make fresh insights into understanding aging mechanisms and especially enrich the theory of programmed aging.”

Treating Aging Processes with Antivirals and Gene Therapies

Our species has evolved with mutations and deletions in ERVs to silence them, mostly eliminating their harmful effects. The most recently inherited ERVs haven’t undergone evolutionary pressures to silence them, which could make their sequence activation during aging potent drivers of senescence. Finding ways to suppress ERVs as we age could be a promising way to thwart ERV-driven senescence.

Programmed aging theory postulates that aging is a treatable condition and that by unraveling biological mechanisms of aging like ERV activation, we can mitigate aging’s effects on our bodies. Gene therapies like CRISPR can be used to inhibit ERV sequences that resurrect during aging to potentially rejuvenate tissue. Promisingly, abacavir restored age-related deficits like grip strength and short-term memory in mice, making potent antiviral drugs promising anti-senescence agents.