- Living a Longer Better Life with Exercise

- Resistance Exercise for Muscle and Bone Health

- Aerobic Exercise for Cardiovascular Health

Living a Longer Better Life with Exercise

It’s no secret that cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality worldwide. Fortunately, exercise is one of the most effective methods for preventing CVD. Exercise can also prevent or reduce the risk of other leading causes of death such as diabetes and cancer. In fact, exercise and physical activity have been shown to reduce the risk of all-cause mortality — death from any cause.

Corroborating the benefits of regular exercise are elite athletes who exemplify the pinnacle of physical fitness. It ends up that elite athletes, especially endurance and mixed sports athletes, have superior lifespan outcomes. Furthermore, a study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine found that American Olympic athletes live about five years longer than the general population. These studies illustrate the importance of physical activity and fitness in living a longer better life.

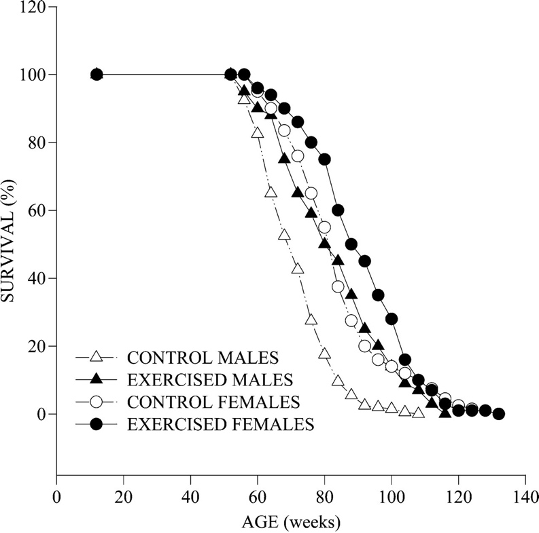

While these human studies do not prove that exercise prolongs lifespan, animal studies are the closest we have. For example, one study showed that moderate exercise on a treadmill increased the lifespan of mice. Still, another study showed that exercise did not increase the lifespan of mice. This lack of lifespan extension was partially owed to the fact that the researchers did not force the mice to exercise. This could mean that lab mice, that need not worry about foraging for food to survive, are comfortable with not exercising. Fortunately, seemingly unlike mice, we can force ourselves to exercise.

It follows that if one wishes to increase the probability of living a long and healthy life, consistently exercising over a lifetime is essential. Physical exercise can be divided into two main categories: resistance exercise and aerobic exercise. While there is considerable overlap, aerobic exercise tends to promote cardiovascular health, while resistance exercise tends to promote muscle and bone health. For longevity purposes, both are necessary to maximize the anti-aging benefits of exercise.

Resistance Exercise for Muscle and Bone Health

When young, many of us have a natural proclivity towards taking our mobility for granted. Thus, the health of our musculoskeletal (muscle and bone) system is often neglected until it is too late. Furthermore, while the benefits of aerobic exercise, especially on the cardiovascular system, are well known and somewhat easily implemented, just how to go about an exercise routine that promotes musculoskeletal health is not as straightforward.

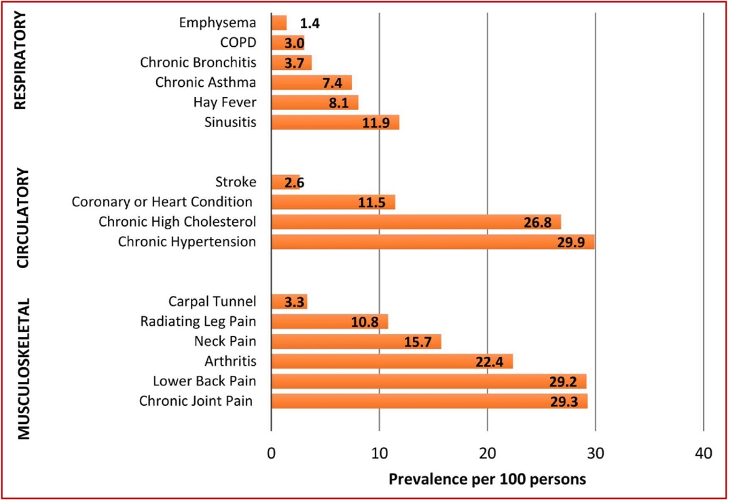

It is estimated that about half the United States population suffers from a musculoskeletal disorder, including back pain, chronic joint pain, and arthritis. However, these ailments may be alleviated or possibly prevented by resistance training (RT) — working against a weight or force to gain muscle and bone strength. RT not only counters musculoskeletal disorders but also other conditions like obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Indeed, the causes of musculoskeletal disorders are one and the same with obesity, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and some cancers. Such root causes include physical inactivity (including a lack of aerobic and RT exercise), poor nutrition, poor sleep, high stress, poor social connections, and the use of tobacco and excessive alcohol. Therefore RT, especially when combined with aerobic exercise, good sleep, and eating well, can potentially delay, prevent, or even reverse many medical complications.

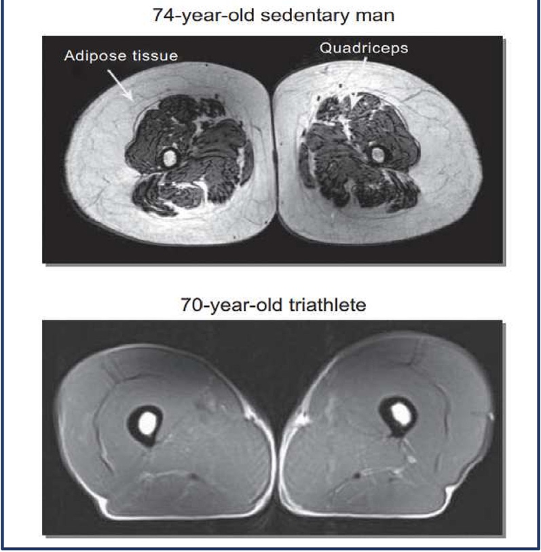

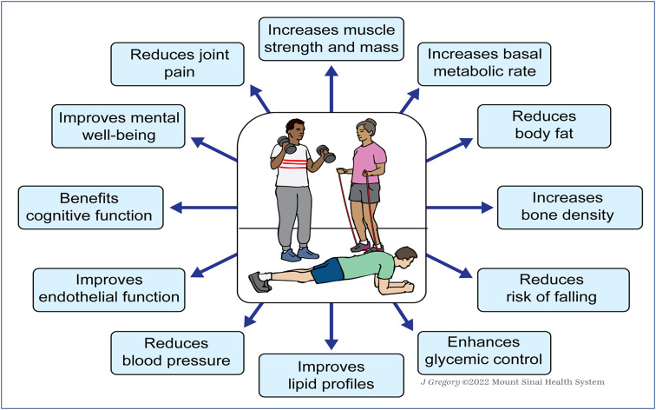

Anti-Aging Benefits of Resistance Training

Without RT, our muscle mass is estimated to decline 3-8% per decade after the age of 30. And with a loss of muscle size (atrophy) comes a loss in muscle strength, contributing largely to losses in everyday mobility. One aspect of mobility — balance is lost with age due to muscle inflexibility and joint stiffness. Also with age, our muscles tend to accumulate fat, further contributing to losses in muscle strength. Moreover, our bones lose approximately 1-3% of their density per year, making them weaker and prone to break.

RT not only increases the size and strength of our muscles, but it also improves bone density for stronger bones, reducing the risks of osteoporosis. Furthermore, since RT improves fat metabolism, it decreases the risk for metabolic disorders like type 2 diabetes. Additionally, by improving the function of our arteries (endothelial function), RT can improve resting blood pressure, potentially alleviating high blood pressure.

RT can also improve cognitive abilities like learning and memory. For example, a study of older individuals participating in RT showed that each increase in muscle strength was associated with a 43% decrease in Alzheimer’s risk and a 33% decrease in cognitive impairment risk. RT can also promote higher self-esteem and a sense of liveliness while reducing depressive and anxious thoughts.

Additionally, by increasing the size of our muscles, we can burn more calories while not exercising. This is because our muscles account for much of what is called our basal metabolic rate (BMR). Our BMR can be thought of as the amount of energy our organs consume to maintain their function. The amount of energy our muscles consume depends on their size, so increasing muscle size increases the energy (calories) they consume.

Interestingly, a recent study showed that strength training rejuvenates the skin better than aerobic exercise. This study emphasizes the unrealized and perhaps surprising benefits of RT. Furthermore, as biological aging research continues to mature, scientists are bound to discover more measurable beneficial effects of RT.

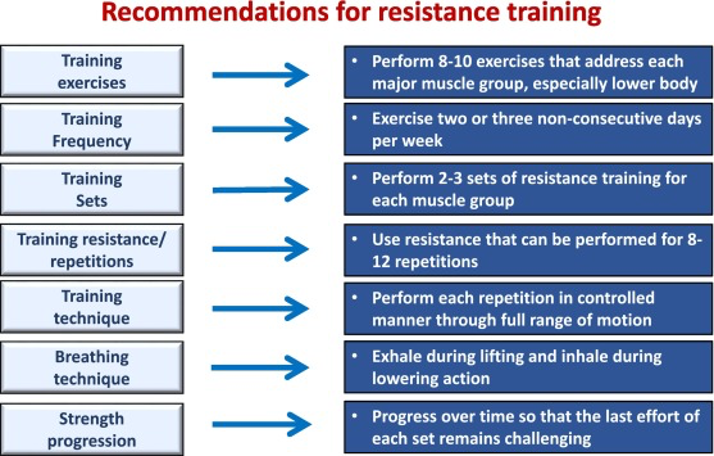

Resistance Training Guidelines

Because form and technique are of utmost importance for executing RT exercises safely and correctly, a personal trainer or other qualified professional is recommended for individuals who are unfamiliar with strength training. To become familiar with the general structure of an RT regimen, the American College of Sports Medicine has provided several guidelines:

In addition to the American College of Sports Medicine’s guidelines, it is crucial to perform RT on a regular basis. Without consistently following an RT training program over the course of weeks and months, it is unlikely that any noticeable benefits will be realized. Moreover, to counter the effects of aging on muscle and bone, the RT program of choice should be incorporated into one’s lifestyle and maintained over a lifetime.

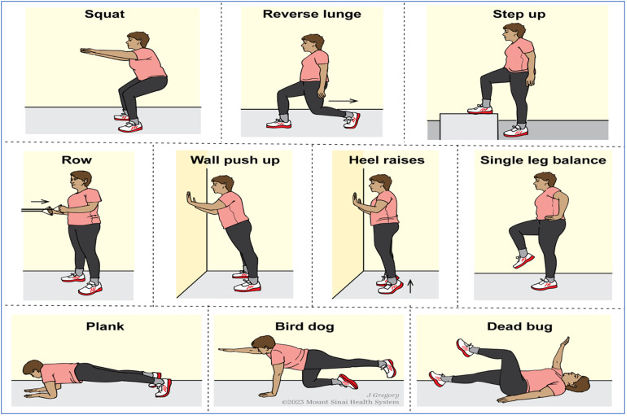

The specific exercises used in an RT routine can vary widely and do not require specialized equipment that would usually be found in a gym. Some exercises only require elastic bands, free weights, or even just body weight. In this way, it may be easier to incorporate specific exercises into one’s lifestyle. For example, some exercises can be done on a lunch break or whenever free-time is available. Examples of these exercises are shown below.

Aerobic Exercise for Cardiovascular Health

The term “cardio” refers to cardiovascular conditioning, which is done via aerobic exercise. Aerobic exercises include swimming, jumping jacks, dancing, or any exercise that requires our cells to utilize oxygen for producing cellular energy. This is opposed to anaerobic exercises like most RT exercises, whereby cellular energy is predominantly produced from sugars stored in our muscles in the form of glycogen. However, unlike glycogen, which eventually runs out, oxygen is unlimited as long as we keep breathing. Thus, aerobic exercise encompasses endurance exercise.

Anti-Aging Benefits of Aerobic Exercise

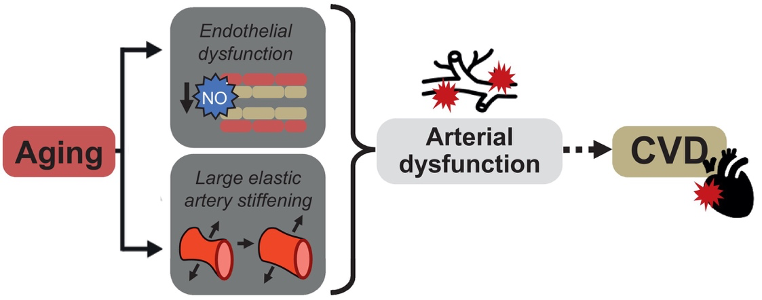

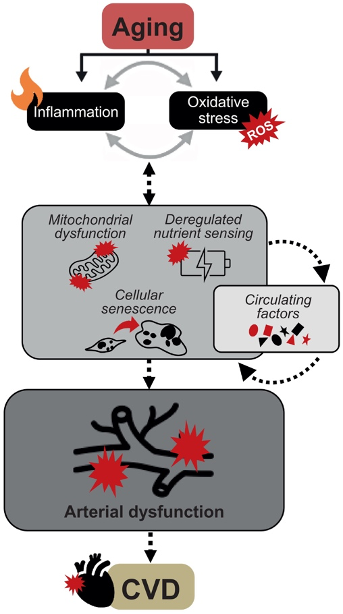

Our cardiovascular system, which includes our heart and vascular system (arteries, veins, and capillaries), is responsible for nourishing every cell in our body with oxygen. With each beat, our heart pumps oxygen-rich blood through our arteries, which distribute the blood to each of our organs. However, with age, our arteries become less elastic and more stiff, leading to the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Furthermore, artery dysfunction can also lead to conditions like cognitive impairment, dementia, chronic kidney disease, and insulin resistance.

Cardiovascular dysfunction is primarily mediated by oxidative stress — excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause damage to our cells. Moreover, ROS react with nitric oxide (NO), a gas produced by blood vessel (endothelial) cells to dilate our arteries. Consequently, by inhibiting NO, ROS contributes to artery stiffness and dysfunction. Age-related chronic low-grade inflammation also contributes to artery dysfunction, feeding into oxidative stress in a vicious cycle.

Preventing Cognitive Decline and Dementia

Exercise has been shown many times to improve cognitive function and can therefore be used as a preventative therapy or treatment for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia. A recent study showed that there is no lower threshold for how much exercise is needed for its neuroprotective effects. This means that getting any bit of exercise is better than none.

Furthermore, RT appears to be superior to other forms of exercise when it comes to improving cognition in healthy older adults. Another study revealed that aerobic exercise combined with RT benefits individuals with MCI, while RT alone is most beneficial for those with dementia. Moreover, exercise stimulates neural plasticity — when new connections are made in the brain, which protects against neurodegeneration and cognitive decline.

Countering Oxidative Stress and Inflammation

Cardiovascular dysfunction is primarily mediated by oxidative stress — excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause damage to our cells. Moreover, ROS react with nitric oxide (NO), a gas produced by blood vessel (endothelial) cells to dilate our arteries. Consequently, by inhibiting NO, ROS contributes to artery stiffness and dysfunction. Age-related chronic low-grade inflammation also contributes to artery dysfunction, feeding into oxidative stress in a vicious cycle. However, aerobic exercise counters oxidative stress and alleviates inflammation.

The primary generator of excess ROS during aging is dysfunctional mitochondria. Normally, mitochondria generate low levels of ROS, which are neutralized by antioxidants. However, mitochondria become less efficient with age and begin generating excess ROS that our antioxidant defenses can’t adequately handle. Subsequently, oxidative stress ensues, whereby excess ROS oxidize and damage proteins, fats, and DNA within cells. However, aerobic exercise counters oxidative stress by restoring mitochondrial health and halting the excess generation of ROS.

Boosting NAD+ Levels

Also contributing to excess ROS is a key molecule essential for mediating the efficiency of mitochondria called nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+). NAD+ carries energy in the form of electrons to and from different areas of mitochondria. However, NAD+ concentrations decline with age, contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction. Moreover, NAD+ is fuel for an enzyme called sirtuin-1, critical for mitochondrial health. NAD+ depletion, considered an aspect of deregulated nutrient sensing, is linked to age-related cardiovascular dysfunction.

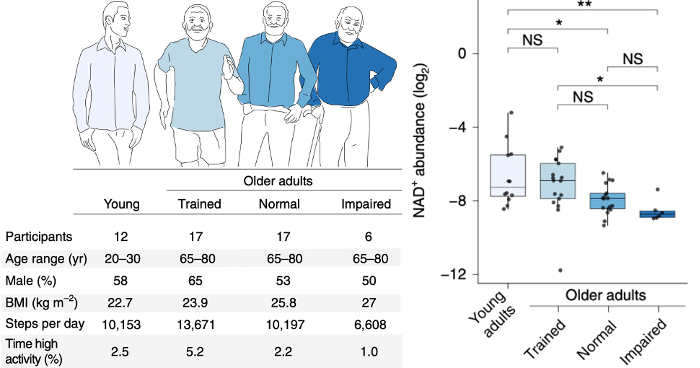

When it comes to boosting NAD+ levels, one study showed that older adults who exercised at least 3 hours per week (trained) had similar NAD+ levels to young adults. However, older adults who exercised 1 hour per week (normal) or less than 1 hour per week (impaired) had lower NAD+ levels than young adults. Furthermore, the same study showed that the number of steps walked per day correlated with an increase in muscle NAD+ levels. Therefore, it seems that getting more steps in and exercising at least 3 hours per week may be advantageous for boosting NAD+ levels.

For young adults, 20 minutes of cycling was shown to raise NAD+ levels. However, the same did not occur in older adults.

Removing Senescent Cells

Senescent cells also contribute to age-related inflammation and tissue damage. Senescent cells are generated in response to cellular stressors like DNA damage, whereby normal cells enter a senescent state, stop functioning normally, and begin secreting a host of molecules known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). The SASP includes pro-inflammatory molecules that contribute to age-related inflammation.

The SASP also spreads senescence to surrounding cells and is implicated in age-related artery dysfunction and CVD. Circulating factors, which may include SASP factors and other inflammatory proteins, are factors in our bloodstream also associated with CVD.

At least two studies suggest that higher intensity exercise is necessary to remove senescent cells. One study showed that high-intensity aerobic exercise is necessary to reduce senescent cell load. In this study, sedentary young men participated in either steady-state cycling —10 minutes with 60% effort — or high-intensity interval cycling — 20-second burst at 120% effort with 20 second rest in between up to 15 times. The results showed that only the men who participated in high-intensity interval cycling saw a reduction in senescent cells.

Mitigating Arterial Dysfunction

Exercise also increases the availability of NO. As a result of aerobic exercise, older adults have been shown to have the same level of endothelial function and arterial stiffness as young adults. Thus, aerobic exercise reduces the risk of CVD and can potentially prevent CVD if action is taken during earlier stages of life.

How Much Aerobic Exercise is Necessary?

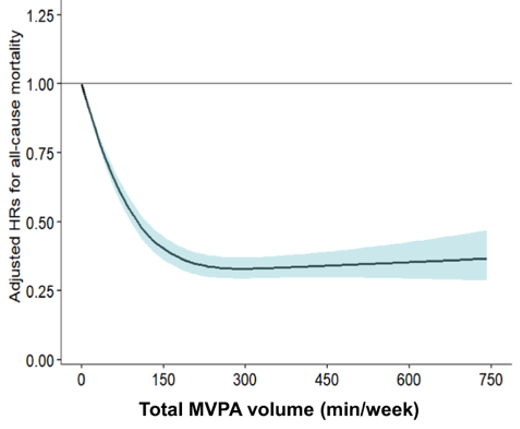

The Department of Health and Human Services recommends that adults participate in at least 75 to 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic exercise per week in addition to RT. Examples of moderate exercise include walking briskly (4 mph) or bicycling slowly (10-12 mph), while vigorous exercise includes hiking, jogging (6 mph), or bicycling fast (14-16 mph). However, “moderate” and “vigorous” are subjective terms that depend on one’s fitness level.

Just Move

When it comes to physical activity, doing something is better than nothing. One study showed that a 1-to-2-minute burst of movement three times per day reduces the risk of death from cancer or CVD. Another study showed that just 11 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity reduces the risks of all-cause mortality. These studies suggest that just a little exercise per day can potentially extend one’s lifespan. However, it seems like this physical activity needs to reach a specific level of intensity. Such activities could include jumping jacks, or jogging up and down some stairs.