Highlights

- Neurogenesis declines and senescent “zombie” cells accumulate with age in the hippocampus, a brain region associated with learning and memory.

- A drug that destroys senescent cells, ABT-263, restores neurogenesis in the hippocampus by rejuvenating brain stem cells.

- Likely through this mechanism, ABT-263 enhances learning and memory in middle-aged mice.

It is becoming increasingly apparent that senescent “zombie” cells play a critical role in aging. As we age, these senescent cells build up and lead to organ dysfunction and failure. Removing senescent cells rejuvenates the organs and increases lifespan. What does this mean for the brain? Canadian scientists show that our memory could be improved even in middle-age by rejuvenating the hippocampus, the brain region responsible for learning and memory.

In Stem Cell Reports, Fatt and colleagues from the University of Toronto in Canada demonstrate that senescent stem cells accumulate in the brain’s hippocampus and inhibit neurogenesis during aging. Canadian scientists use the senolytic drug ABT-263 to show that removing these senescent stem cells improves learning and memory in middle-aged mice. These findings reveal that even our memories are affected by senescent cells as we age.

Neurogenesis and Brain Stem Cells Decline with Age

Neural precursor cells (NPCs) are brain stem cells important for memory formation and consolidation. One of the hallmarks of memory formation is neurogenesis — the generation of new neurons. Neurogenesis declines rapidly with age; at the same time, there is a decline in NPCs. The reason for this decline has been unclear, so Fatt and colleagues examined the hippocampus, where memory formation and consolidation occur.

By using modified antibodies that fluoresce under specific wavelengths of light against various proteins known to be associated with neurogenesis, Fatt and colleagues showed that neurogenesis in the hippocampus of mice declines rapidly with age. Using a similar technique, NPCs were found to become dysfunctional with age, confirming previous findings.

Senescence Increases with Age

Senescent cells are former ordinary cells that have gone into a senescent “zombie-like” state due to various stimuli, such as stress. Senescent cells are growth-arrested and can no longer proliferate — grow and multiply. They secrete multiple signaling molecules, some of which affect surrounding non-senescent cells.

A key finding in the decline of neurogenesis and NPCs that Fatt and colleagues observed was the inability of some NPCs to proliferate with age. For this reason, the Toronto-based researchers searched for signs of senescence using various fluorescent and genetic markers. They found that more and more NPCs become senescent in the mouse hippocampus with increasing age. Senescence is likely why the NPCs do not proliferate and hinder neurogenesis.

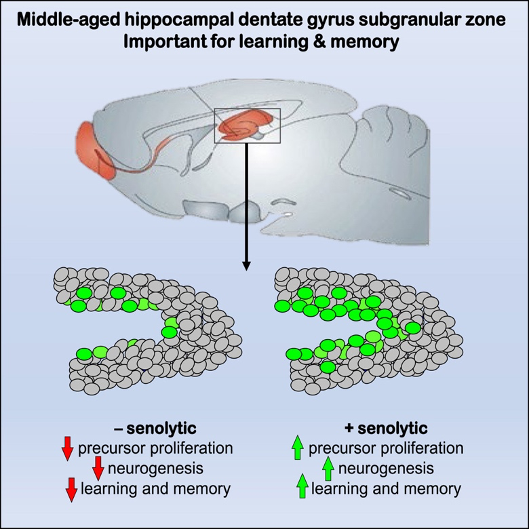

(Fatt et al., 2022 | Stem Cell Reports) Senolytic Drug Improves Learning and Memory. Without the senolytic drug ABT-263, neural stem cells do not proliferate, decreasing neurogenesis and inhibiting learning and memory. By eliminating senescent neural stem cells, ABT-263 rejuvenates proliferation, increases neurogenesis, and improves learning and memory.

ABT-263 Reduces Senescent NPCs and Increases Neurogenesis

ABT-263 (Navitoclax) eliminates senescent cells by causing cell death and, for this reason, is considered a senolytic drug. Senolytic drugs, also called senolytics, are a class of drugs that eliminate senescent cells. To determine the effect of clearing out senescent NPCs in the hippocampus of mice, Fatt and colleagues injected mice with ABT-263. They found that the ABT-263 reduced the number of senescent cells, resulting in enhanced proliferation and increased neurogenesis in young and middle-aged mice.

ABT-263 Improves Spatial Memory

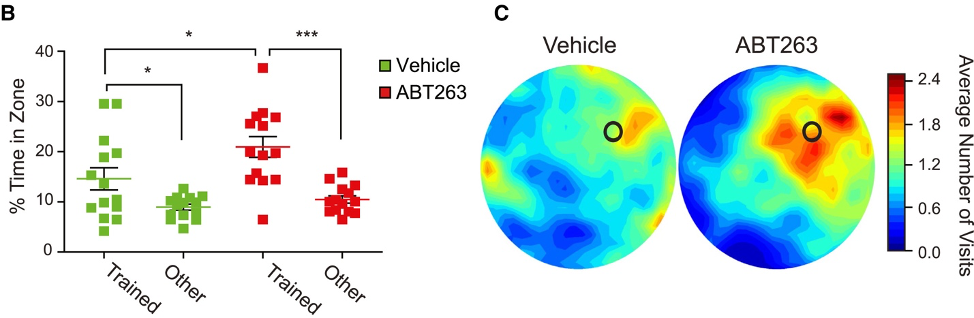

To determine the effect of removing senescent cells from the hippocampus on learning and memory, Fatt and colleagues used the Morris water maze test. The Morris water maze test involves training a mouse to find a submerged platform in a pool of water for several days. After the training/learning, the platform is removed, and the mouse is then placed into an empty pool. While in the pool, the researchers measure the amount of time the mouse spends swimming in the former location of the platform — the trained zone.

Fatt and colleagues showed that middle-aged mice given the senolytic ABT-263 spent more time in the trained zone than other zones. These findings suggest that senescent cells accumulated in the hippocampus of middle-aged mice hinder learning and memory and that removing the senescence cells restores learning and memory.

(Fatt et al., 2022 | Stem Cell Reports) ABT-263 Improves Learning and Memory. (left) The graph shows the percentage of time spent searching the correct (Trained) versus incorrect (Other) former location of the platform in untreated (Vehicle) and ABT-263 treated middle-aged mice (ABT263). Mice treated with ABT-263 spent more time in the correct location, showing memory improvement. (right) Visual representation of mouse swimming location. Red indicates the correct area.

Senescence the Culprit for Yet Another Symptom of Aging

The findings of Fatt and colleagues may explain why deficits in learning and memory come with aging and neurodegenerative disease. NPCs in the hippocampus become senescent and can no longer generate new neurons. Also, the molecules secreted by senescent NPCs could stop the surrounding non-senescent cells from making new neurons. Both of these effects inhibit neurogenesis by blocking the generation of new neurons. By inhibiting neurogenesis, learning and memory are compromised.

“When we improve the neighborhood by getting rid of deleterious cells in the stem cell niche, we begin to mobilize and wake up the dormant stem cells, enabling them to generate new neurons for spatial learning and memory,” says the senior author, Dr. David Kaplan.

Senolytic Drugs a Potential Treatment for Learning and Memory Loss

ABT-263 was developed to treat cancer and is safe in humans. Senolytic drugs like ABT-263 are currently in clinical trials to treat arthritis, diabetes, pulmonary fibrosis, and chronic kidney disease. That senolytics seem safe for humans and can treat multiple organs makes them a good candidate for treating age-related brain decline and learning/memory deficits.

The findings of Fatt and colleagues showed that memory and learning could be restored in middle-aged mice, but they did not investigate aged mice. Since senescent cells accumulate with aging, it may be possible that the effect of removing senescent cells would be even greater in aged mice.

Either way, the findings suggest that senescent cells affect our ability to learn and remember even in middle age. For this reason, it is possible that taking senolytic drugs earlier in life could help prevent the learning and memory loss that occurs with age. There are already plans to use senolytics in clinical trials for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, so this possibility does not seem too far-fetched.