Key Points

- The CALERIE trial examined 220 adults without obesity who either restricted caloric intake by 25% or ate freely for 2 years.

- The intervention represented a 2–3% slowing in the pace of aging, which translates to a 10-15% reduction in mortality risk (an effect similar to a smoking cessation intervention).

- There was no significant difference in biological age estimates between calorie-restricted and freely-eating adults as measured by various aging clocks.

Calorie restriction, which has been shown to slow aging in animals, showed signs of slowing biological aging in the first-ever study of the effects of long-term calorie restriction on healthy, non-obese humans, shows a study published in Nature Aging. The two-year Phase 2 randomized controlled trial found that the intervention effect represented a 2-3% slowing in the pace of aging, which in other studies translates to a 10-15% reduction in mortality risk, an effect similar to a smoking cessation intervention. The CALERIE trial was funded by the US National Institute on Aging (NIA) and led by researchers at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health.

Cutting Calories to Curb Aging

Aging researchers have proposed that slowing or reversing the changes at the level of cells and molecules that come with getting older could delay or stop a number of chronic diseases and make people live longer and healthier lives. Multiple therapies with the potential to improve human health have been identified through aging biology research.

One such therapy is caloric restriction. Curbing caloric intake causes changes in molecular processes that have been linked to aging, such as DNA methylation, and has been shown to increase the healthy lifespan—at least in many species of animals. “In worms, flies, and mice, calorie restriction can slow biological processes of aging and extend healthy lifespan,” says senior author Daniel Belsky, PhD, an associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia Mailman School and a scientist with Columbia’s Butler Aging Center.

A barrier to advancing the translation of caloric restriction and other anti-aging therapies through human trials is that intervention studies run for months or years, but human aging takes decades to cause diseases.

Caloric Restriction Has Anti-Aging Effects in Humans

The CALERIE (Comprehensive Assessment of Long-Term Effects of Reducing Intake of Energy) study wanted to find out if calorie restriction also slows biological aging in humans. The trial randomized 220 healthy men and women at three sites in the U.S. to a 25 percent calorie restriction or normal diet for two years.

Belsky’s team looked at blood samples taken from CALERIE Trial participants before the intervention and after 12 and 24 months to figure out how fast their bodies were aging. Belsky and his team used published algorithms to try to figure out how the gradual loss of system integrity that comes with aging is caused by the accumulation of molecular changes. All of these things show strong links with morbidity and mortality related to aging.

“Humans live a long time,” explained Belsky, “so it isn’t practical to follow them until we see differences in aging-related disease or survival. Instead, we rely on biomarkers developed to measure the pace and progress of biological aging over the duration of the study.”

The team analyzed marks on DNA (called methylation) extracted from the participants’ white blood cells using several algorithms that quantify biological age and the pace of aging. The goal of analyzing DNA methylation, which are chemical tags on the DNA sequence that control how genes are expressed and change with age, in CALERIE was to measure the effects of anti-aging interventions at the molecular level.

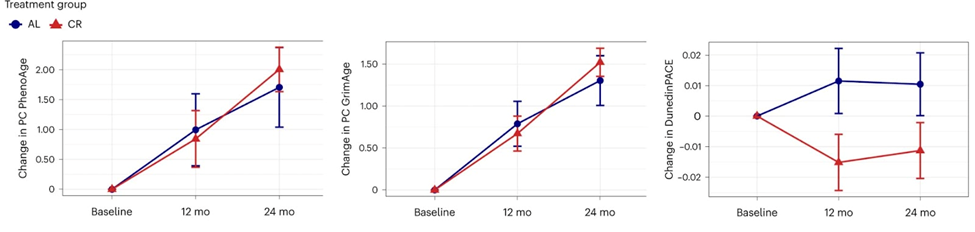

To quantify biological aging, the team used two algorithms called PhenoAge and GrimAge that are known as aging clocks. They also looked at the pace of aging using an algorithm called DunedinPACE.

These three measures of DNA methylation were made using different methods and are based on different ideas about how people age. The PhenoAge and GrimAge clocks were made to predict the risk of death at a single time point in adults of different ages and adults who are older. This approach quantifies aging as a static construct of risk accumulated across a lifetime. DunedinPACE, on the other hand, was made to predict the decline of multiple physiological systems over 20 years of follow-up, from early adulthood to midlife. This approach quantifies aging as a dynamic construct reflecting changes in risk accumulation.

The CALERIE intervention slowed the pace of aging by 2–3% as measured by DunedinPACE, whereas the calorie restriction intervention did not affect the PhenoAge and GrimAge DNA methylation clocks. Previous studies have shown that a 2–3% slower rate of aging as a result of the CALERIE treatment is equivalent to a 10–15% lower risk of dying, which is about the same size as the effect of helping people stop smoking.

“In contrast to the results for DunedinPace, there were no effects of intervention on other epigenetic clocks,” noted Calen Ryan, PhD, Research Scientist at Columbia’s Butler Aging Center and co-lead author of the study. “The difference in results suggests that dynamic ‘pace of aging’ measures like DunedinPACE may be more sensitive to the effects of intervention than measures of static biological age.”

Since follow-up in the CALERIE Trial did not extend beyond the intervention, it is therefore unclear if the changes in DunedinPACE observed during the 2-yr intervention will translate into reduced morbidity and mortality over the long term. Additional follow-up of trial participants is required to determine whether CR-induced reductions to DunedinPACE in CALERIE will translate into disease prevention and increased healthy lifespan. In observational studies with long-term follow-up, individuals with slower DunedinPACE are better off on a range of healthspan metrics, including showing a reduced incidence of morbidity and increased survival.

Calorie Restriction Isn’t For Everyone

“Our study found evidence that calorie restriction slowed the pace of aging in humans” Ryan said. “But calorie restriction is probably not for everyone. Our findings are important because they provide evidence from a randomized trial that slowing human aging may be possible. They also give us a sense of the kinds of effects we might look for in trials of interventions that could appeal to more people, like intermittent fasting or time-restricted eating.”

The authors say that even though the effects of the treatments were small, even a small slowing of aging can have big effects on the health of a whole population. Ultimately, a conclusive test of the geroscience hypothesis will require trials with long-term follow-up to establish the effects of interventions on primary healthy-aging endpoints, including incidence of chronic disease and mortality. The evidence reported from CALERIE suggests that DunedinPACE may be helpful in identifying short-term interventions worthy of long-term follow-up to generate such evidence.