Key Points:

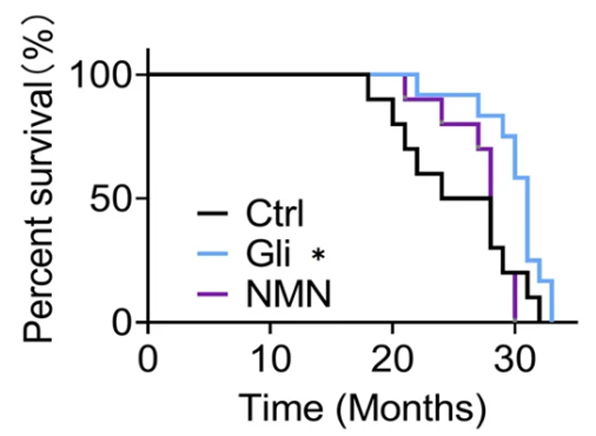

- Glyburide prolonged the average lifespan by nearly 20% in aged mice.

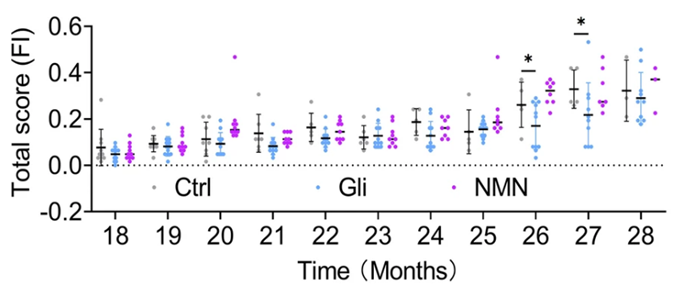

- Glyburide reduced frailty in aged mice, while nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) treatment did not confer significant effects against frailty.

- Glyburide also lowered liver scarring (fibrosis), a sign of aging, in older mice.

Dysfunction of the cell’s powerhouse—mitochondria—is a hallmark of aging and has been tied to age-related neurodegenerative disorders, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic conditions. Interestingly, the diabetes drug chlorpropamide has been shown to exert effects against aging in worms by altering mitochondrial function. This finding has drawn attention to the class of diabetes medications to which chlorpropamide belongs—sulfonylureas—for possible aging intervention properties.

Along those lines, Li and colleagues from Shihezi University in China published in Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy findings that an anti-diabetes sulfonylurea, glyburide (also known as glibenclamide), extends mouse lifespan. The research team also showed that glyburide significantly reduced frailty in aged mice, while the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) precursor, NMN, did not. Furthermore, glyburide reduced liver fibrosis, a sign of aging, in older mice. The findings from Li and colleagues suggest that this common diabetes medication may exert effects against aging.

Glyburide Extends Mouse Lifespan, Reduces Frailty, and Lowers Liver Fibrosis

Because of the anti-aging properties of the diabetes medication chlorpropamide, which targets the mitochondrial protein MDH2, Li and colleagues analyzed how other related drugs interact with MDH2 in human cells. The researchers found that one drug in particular, glyburide, showed an elevated interaction with MDH2. Because glyburide targets MDH2 similarly to chlorpropamide, the China-based researchers performed further tests of glyburide’s potential effects against aging.

One of the best indicators of potential pro-longevity properties is to measure a drug’s effects on lifespan. In that regard, Li and colleagues injected glyburide into the stomachs of mice. The team found that these glyburide injections extended the average lifespan of mice by about 20%. This finding suggests that indeed, glyburde promotes lifespan extension.

To assess whether glyburide promotes the enhancement of physical function in older mice, Li and colleagues measured the frailty index—a test that quantifies health deficits. Frailty indices are measured on a scale of 0 to 1, with lower scores suggesting better physiological function. Accordingly, aged mice showed better frailty index scores at 26 and 27 months of age (roughly equivalent to 73 to 75 years of age for humans) with glyburide treatment. Moreover, NMN did not improve frailty index scores. These findings suggest that glyburide prolongs healthspan—the duration of life without an age-related disease.

To gain a better handle on whether glyburide improves other markers of aging, Li and colleagues tested whether this anti-diabetes drug reduces liver fibrosis. Intriguingly, glyburide lowered fibrosis in older mice. This finding supports that glyburide reduces liver fibrosis, a key sign of aging.

Human Trials Will Be Necessary To Test Whether Glyburide Exerts Aging Intervention Properties In Humans

Li and colleagues identified glyburide, a common anti-diabetes drug, based on its interaction with the mitochondrial protein MDH2, which plays a role in cell energy-generating reactions. Through its interactions with MDH2, other data from the study showed that glyburide alters mitochondrial metabolism and reduces protein markers of senescent cells—dysfunctional cells that accumulate in tissues with age. Thus, possibly through its effects on metabolism, glyburide may reduce senescent cell abundance to improve tissue function.

The accumulation of senescent cells, another hallmark of aging, has been associated with age-related organ deterioration. In that sense, glyburide could reduce senescent cells in organs like the liver and possibly others to improve healthspan and perhaps even lifespan.

Whether glyburide confers similar effects in humans awaits human trial testing. In that sense, the preclinical data provided by Li and colleagues in this study may support testing glyburide’s effects in humans with trials. This could mean that glyburide supports longevity even in people without diabetes. In that regard, some longevity enthusiasts without diabetes take the diabetes medication metformin, repurposed for longevity promotion. As such, the findings from Li and colleagues could trigger the repurposing of another anti-diabetes drug, in this case, glyburide, for people seeking to extend their healthspans and perhaps lifespans.