Key Points:

- An FDA-approved insulin signaling inhibitor (alpesilib) extends male and female mouse lifespan.

- Alpesilib also affected certain markers of aging indicative of improved healthspan.

- It is unclear if alpesilib will translate to humans because of inter-species differences in the relationship between sugar levels and lifespan.

Researchers may have discovered a pill that can increase human lifespan by 10%, or 7 to 8 years.

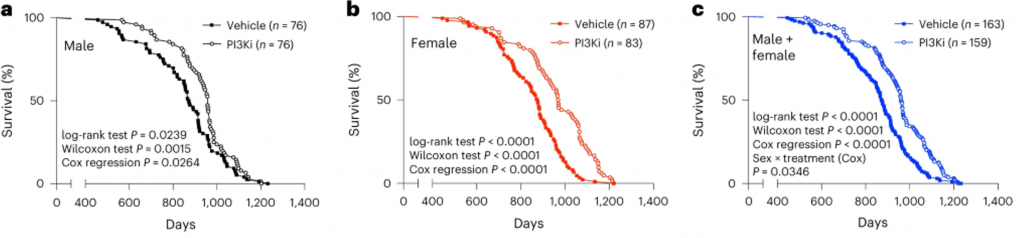

A new study suggests that such a pill could soon be headed for clinical testing, as researchers from the University of Auckland, New Zealand, show that supplementing food with an FDA-approved compound called alpelisib can increase the average lifespans of middle-aged mice by roughly 10%. In this study, which was published in Nature Aging, alpesilib also helped improve balance and coordination, which are important signs of aging.

“We were pleased to see this drug treatment not only increased longevity of the mice, but they also showed many signs of healthier aging,” said research fellow Dr. Chris Hedges.

This research is important because only a few drugs have been shown to lengthen the lives of both male and female mice consistently.

Insulin Inhibitors, Invertebrates, and Impeding Cancer

Invertebrates like roundworms and flies live longer when their insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1) signals are shut down. However, whether it is a feasible longevity target in mammals has been unclear.

Clinically, compounds that target a key component of insulin signaling, called phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110 inhibitors (PI3Ki), are being used as therapeutics. For example, the FDA has approved alpelisib, an oral PI3Ki, to treat an advanced form of breast cancer in which the insulin signaling pathway has been dysregulated.

The Anti-Aging Alpelisib

Here, Hedges and colleagues use alpelisib to test the idea that long-term inhibition of PI3K would increase the lifespan and overall health of mice. Researchers from the University of Auckland show that adding PI3Ki alpelisib to a mouse’s diet starting in middle age makes the average length of life longer. This effect is stronger in female mice. Alpelisib increased the maximum lifespan of the whole group and of females on their own, but not of males.

Independent of food intake, alpelisib led to a loss of body weight that was evident after one month of treatment in males and six months in females. Mouse body weights begin to decline around 20 months of age, and this age-related loss of body weight and muscle mass is linked to an increased risk of death and a shorter life span. When Hedges and colleagues looked at whether alpelisib altered the rate of weight loss at 20 months of age, they found that supplemented male mice had a slower age-related loss of body weight than vehicle mice, while supplemented female mice had an increased rate of age-related body weight loss.

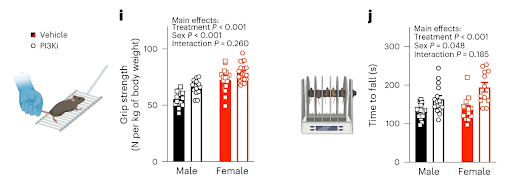

When mice were given alpelisib as a supplement to their food, their strength, balance, and coordination all got better. It also made some common signs of aging in people worse, like losing bone mass and having slightly high blood sugar, while having little to no effect on exercise capacity, heart function, and cognition. This is important to keep in mind when thinking about how these findings can be used, since osteoporosis is a major age-related disease in humans that shortens both healthspan and lifespan.

Clinical Utility and Caution

It is important to note that there is a glaring issue with this research, which is that the relationship of blood sugar levels to longevity in mice is flipped for humans and primates. This means that higher blood sugar levels have been linked to a lower risk of death in mice, but the opposite is true for primates and humans: lower blood sugar levels are linked to longer lives. These results show that while blocking insulin signaling could be a good way to slow down some parts of aging, compounds like alpelisib should be used with caution in people.

In short, this work shows that long-term targeting of insulin signaling during aging is safe and can make male and female mice live longer on average. Since alpelisib is already used to treat some types of cancer, the authors want to find out how long-term use affects signs of aging in people.

“We have been working on developing drugs to target [insulin signaling] for more than 20 years as evidence indicated they would be useful to treat cancers as many cancers have an excess activation of this pathway,” said Professor Peter Shepherd, who was also involved in the research. “Therefore, it’s great to see that these drugs might have uses in other areas and reveal novel mechanisms contributing to age-related diseases.”