Key Points:

- Treatment with the immune protein GM-CSF improves the spatial memory of middle-aged to older mice.

- GM-CSF also improves the memory of a mouse model for Down syndrome.

- Treatment with GM-CSF increases neuronal organization in the hippocampus – a region of the brain associated with memory – in Down syndrome mice.

Most of us hope to maintain our wits about us as we age. While reading books, eating healthy, and exercising will keep us sharp, certain biological interventions may be able to improve our memory as well. As it turns out, such interventions could also potentially be used to treat Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome – a genetic disorder leading to numerous health impacts, including cognitive difficulties.

In a new study out of the University of Colorado, published in Neurobiology of Disease, Ahmed and colleagues show that a medication currently under study for treating cognitive degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease may also improve memory deficits associated with Down syndrome and aging. They found that treatment with GM-CSF (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) – being evaluated in phase 2 clinical trials for Alzheimer’s as sargramostim – improved the memory of middle-aged to older mice and a mouse model for Down syndrome. The treatment also led to increased brain cell organization in the Down syndrome mouse model.

What is GM-CSF?

GM-CSF, also known as sargramostim is a protein secreted by immune cells with both pro- and anti-inflammatory characteristics, as well as immune-modulating properties. Along with its 30 years of FDA-approved use for other disorders, GM-CSF is commonly used to treat low white blood cell counts during chemotherapy. Only in the last 15 or so years has it been studied for its effects on cognitive abilities.

“We are breaking new ground in studying sargramostim for multiple, different disorders – Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease…We hope that this therapy, already proven to be safe for other diseases, will greatly improve cognitive function in people with Down syndrome,” Huntington Potter, PhD, lead researcher, said in a press release.

Spatial Memory and Neuronal Organization Improved by GM-CSF

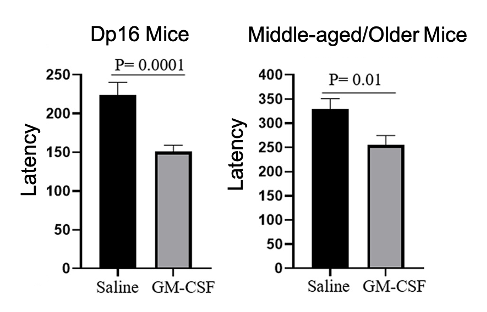

The investigators tested the spatial memory of middle-aged to older mice (12 to15 months old, equivalent to ≥ 58 human years) and Dp16 mice — a mouse model of Down syndrome. The mice were placed into a water maze where they had to locate a hidden platform. When the Dp16 mice were treated with GM-CSF (5 µg/day injection), they required significantly less time to reach the platform. Similarly, the middle-aged to older mice also required significantly less time to reach the platform than their untreated counterparts, indicating improved spatial memory.

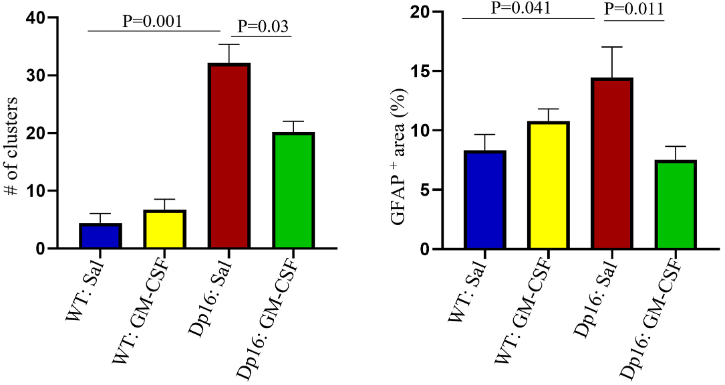

Ahmed and colleagues next harvested the brains of the mice subjected to the water maze test to look for cellular changes that may underly GM-CSF-induced improvements in memory. They examined the hippocampus — the primary brain region associated with memory and learning. The hippocampus, along with the rest of the brain is made up of multiple cell types, including neurons and astrocytes. Astrocytes are the most numerous of brain cells and support the health of neurons, thus playing a critical role in brain function.

Treatment with GM-CSF partially restored the distribution of astrocytes within the hippocampus of Dp16 mice, reversing the clustering often seen in the syndrome, which leads to decreased neuronal functioning. The treatment also reversed astrogliosis, another common change in astrocytes seen in Down syndrome. The number of interneurons — highly localized neurons — were also increased with treatment. Interneurons contribute to neuronal plasticity, a part of learning and memory, so their increases with GM-CSF treatment may play a role in the improved spatial memory seen with treatment. Furthermore, reduced astrocyte clustering and astrogliosis could also contribute to improved brain function, which in the hippocampus would also mean improved spatial memory.

Hope for the Aging Brain

Many of our thinking abilities appear to peak around the age of 30 and start to decline as we age. The most common age-related cognitive deficits are slowness in thinking, difficulties sustaining attention, multi-tasking, information retention, and word-finding. If the findings of Ahmed and colleagues translate to humans, GM-CSF could go a long way towards helping our minds age gracefully.

GM-CSF has beneficial effects on neuronal damage recovery, preventing cell death, restoring cerebral blood flow, and promoting neuronal growth and regeneration. More research is needed before we can say that GM-CSF helps to retain and improve memory and cognition through these underlying changes, although the results of this study seem to show its potential to do so. If so, most older and likely younger individuals may opt in for GM-CSF treatment, especially if it means retaining cognitive abilities with age.