Key Points:

- Core metrics of aging that assess physical and mental function suggest that people from newer generations retain more youthful abilities longer than older generations.

- Researchers assessed the physical and mental function of individuals over the age of 60 from two studies — one conducted in England and the other performed in China.

- These findings contradict previous research suggesting that while life expectancy has increased over the last century, a parallel expansion in the healthy years we live without a debilitating disease or condition (healthspan) has not followed.

Published in a pre-print that is under review by Nature, Moreno-Agostino and colleagues from top-notch institutions like University College London and Columbia University reveal evidence suggesting that older people are currently retaining more youthful abilities compared to those from previous decades. The research team examined a combination of physical and mental abilities — cumulatively referred to as intrinsic capacity.

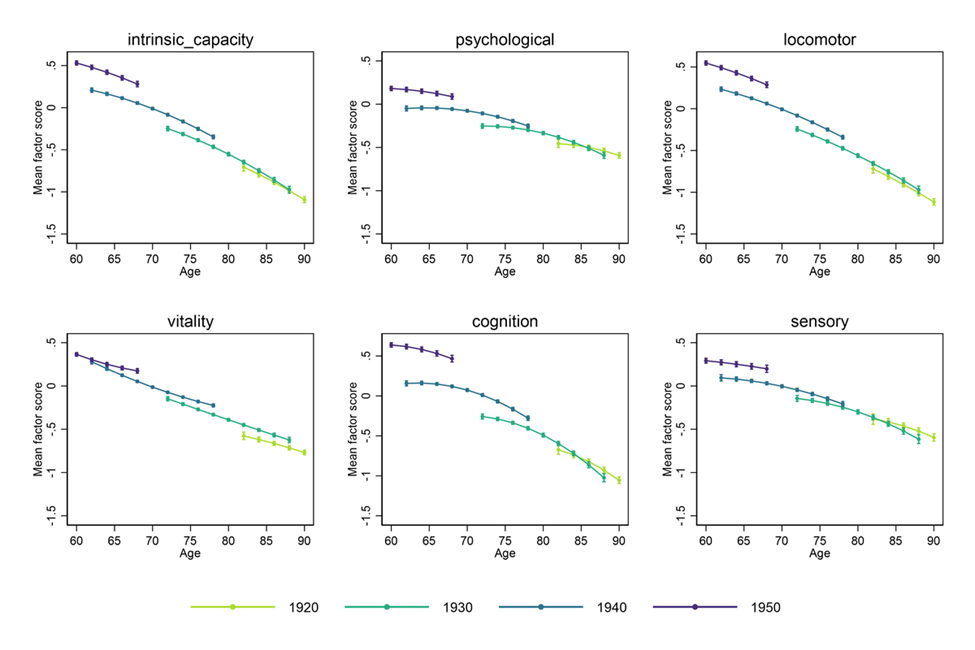

Intrinsic capacity was assessed with metrics like locomotor activity, measured with walking speed and balancing abilities; cognitive capacity, based on memory recall; sensory capacity, assessed with hearing and vision abilities; and psychological capacity, measured with mood and sleep evaluations. Another measurement used to determine intrinsic capacity was called vitality, based on factors like grip strength and lung function.

The Two Studies Combined Evaluated Over 25,000 Aged Adults

To conduct their study, Moreno-Agostino and colleagues utilized data from two large studies of aging individuals — the English Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSA) and the China Health and Retirement Study (CHARLS). The ELSA study contained 14,710 aged adults, while the CHARLS study included 11,411 aged individuals, and participants in both studies were over the age of 60.

For all of the assessments, especially cognitive capacity, participants born in more recent decades exhibited better measurements than those born in earlier decades. When all of the metrics were combined to attain assessments of intrinsic capacity, 68-year-olds born in the 1950s were significantly better off than 62-year-olds born in the 1940s. Moreover, some of the data from English participants suggested that, for groups born more recently, declining physical and mental capacity tapered off slower than for older generations.

Because participants were divided into groups based on the decade they were born (i.e., 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, or 1950s), and since assessments from each group did not overlap, direct comparisons of physical and mental function could not be made between all groups. This meant that some inferences for the rates of physical and mental decline had to be made, which suggested that age 70 for participants born in 1950 is approximately equivalent to age 60 for people born in earlier decades.

“While our models suggest that today’s 70-year-olds have the equivalent functioning to substantially younger adults in previous generations (perhaps 70 really is the new 60), our direct assessments can only confirm that 68 is the new 62,” say Moreno-Agostino and colleagues.

The Study Suggests that Healthspan Has Improved with Extended Life Expectancy

Over the past century, global life expectancy has increased. Early on, increased survival during childbirth as well as childhood accounted for this life expectancy extension, but more recently, it has been due to longer survival at older ages. Such improvements in life expectancy from living longer have been well-documented, but it has been unclear how the health of older adults today compares to that of previous generations at similar ages. Along those lines, some research has suggested that while our lives are getting longer, our healthspans have not improved.

The findings from Moreno-Agostino and colleagues run counter to the prevailing notion that a longer average human lifespan has not been accompanied by improvements in healthspan. A possible explanation for this discrepancy, proposed by Moreno-Agostino and colleagues, is that research suggesting people are living longer without improvements in healthspan only looks at disease prevalence. For this reason, in their study, rather than measuring the prevalence of age-related diseases, the researchers looked at physical and mental capabilities.

According to Moreno-Agostino and colleagues, new treatments could make living with certain age-related diseases or conditions less debilitating and less of a hindrance on physical and mental function. Thus, examining aged adults’ mental and physical capabilities, regardless of whether they have an age-related condition, would help unravel their abilities to perform everyday tasks independently.

The Possibility that Aging Is Occurring Slower for Newer Generations

The most robust evidence for newer generations aging slower than earlier ones comes from the cognitive metric. A possible explanation for this, as Moreno-Agostino and colleagues suggested, could be improved educational opportunities in earlier years for newer generations.

This idea falls in line with the cognitive reserve hypothesis, where people who have higher education levels during their younger years appear to escape the ravages of dementia to a certain degree. As such, educational improvements in younger generations may help enhance cognitive capacity as newer generations age.

Another idea that Moreno-Agostino and colleagues proposed for why intrinsic capacity has increased was that physical activity levels may have improved in newer generations. This, they said, is likely not true, though, since physical activity may have actually declined over time in England, whereas physical activity levels seemed to remain stable in China.

Also, the researchers proposed the idea that medicine is progressively getting better at diagnosing and treating age-related diseases and conditions. For this reason, a higher prevalence of age-related diseases and/or conditions in aged adults could be due to more advanced diagnosis-related technology. What’s more, improved treatments could keep people with age-related ailments alive longer and in a better physical and mental state for longer durations. Hence, more modernized medicine may help retain patients’ functional capacity for longer periods.

Pinpointing an explanation for why newer generations may be retaining more youthful abilities during their golden years compared to older generations is likely a complex task. As such, there may not be a single determinant for this.

At any rate, the findings from Moreno-Agostino and colleagues bode well for all of us as individuals and as a society. On an individual level, most of us would prefer to retain our physical and mental capabilities as we grow older. For society, retaining more youthful physical and mental capacities for a longer period of life could allow individuals to delay retirement. Doing so may help stimulate the economy.

“Our analysis strongly suggests that increasing life expectancy is being accompanied by large increases in health expectancy among more recent cohorts, at least when focusing on people born between 1920 and 1959,” say Moreno-Agostino and colleagues. “This has positive implications for all of us, both as individuals and for society more broadly.”