Key Points:

- Gut microbiota (bacteria) from young mice reduces neuroinflammation in the retinas and brains of aged mice but does not improve cognition.

- Young gut microbiota improves intestinal inflammation and leaky gut in aged mice.

- Fecal matter transplants from young mice improve bacterial composition, and lipid and vitamin synthesis in aged mice.

The bacteria living within our gut can profoundly influence the rest of our body, even affecting the way we age. As our brains age, we become more susceptible to cognitive decline and neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, the underlying cause of which includes inflammation. Now, a new study shows how our gut microbiota could influence the inflammation of our aging brain.

A recent study out of the United Kingdom, published in Microbiome, highlights the importance of the relationship between our gut microbiota and our brains, and the resulting impact on our health as we age. Parker and colleagues performed intestinal microbiota exchanges among young, old, and aged mice. The microbiota exchanges from aged mice to young mice accelerated age-related retinal, central nervous system (CNS), and intestinal inflammation. In contrast, these age-related changes were reversed in aged mice with the transfer of microbiota from young mice.

“This ground-breaking study provides tantalizing evidence for the direct involvement of gut microbes in aging and the functional decline of brain function and vision and offers a potential solution in the form of gut microbe replacement therapy,” the senior author, Simon Carding, PhD, said in a press release.

Gut Microbiota from Young Mice Decrease Inflammation in Old Mice

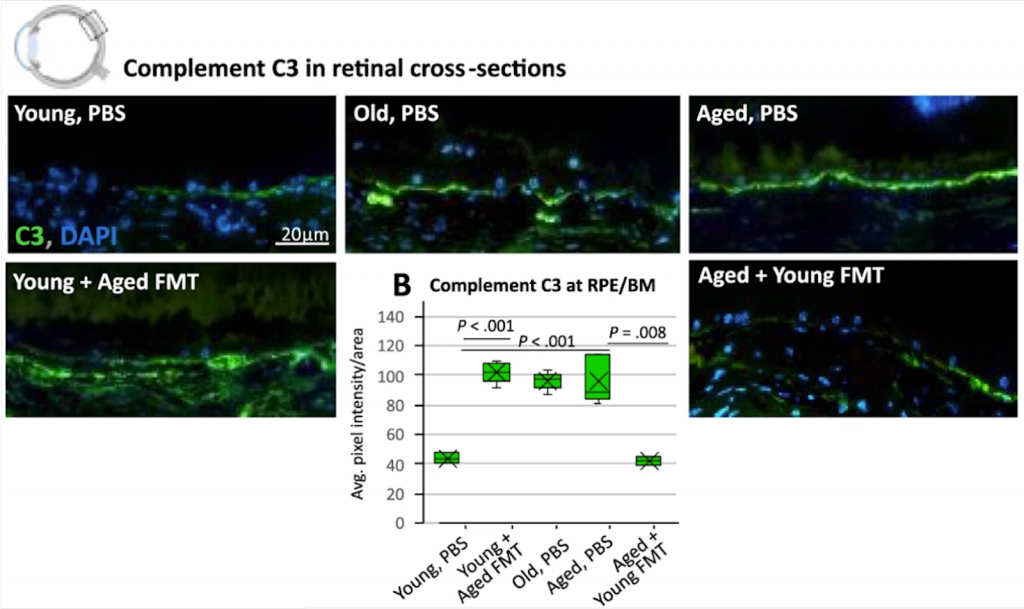

When young mice were given gut microbiota – via fecal matter transplants – from aged mice, their retinas had an increase in complement C3 – an inflammatory protein associated with retinal degeneration. Additionally, microglial cells – immune cells within the brain – were activated, indicative of increased neuroinflammation, a hallmark of aging. In contrast, when aged mice were given gut microbiota from young mice, the aged mice had a decrease in pro-inflammatory molecules, including C3, and decreased microglial activation. While these findings suggest that young gut microbiota restore age-related inflammation in the eye and brain, the aged mice receiving young gut microbiota did not have significant improvements in cognition.

Aging is often characterized by progressive dysfunction of organs and tissues, especially the eyes, CNS, and the gastrointestinal system (which faces an onslaught from environmental insults on a daily basis). The gastrointestinal system, in particular, is well-known to influence the brain via the brain-gut axis – an interesting phenomenon in which the CNS and the intestinal nervous system are linked, connecting emotion and cognition with intestinal function.

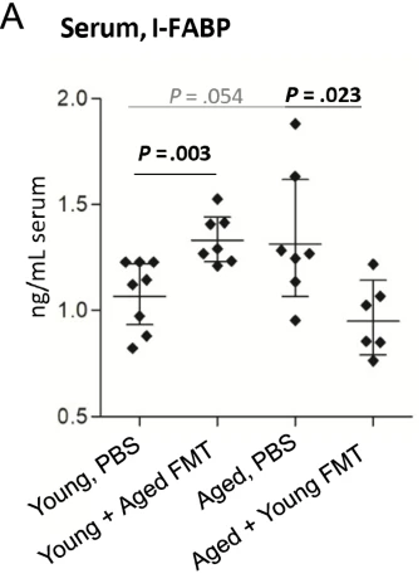

Parker and colleagues next looked at the effect of fecal matter transplants on the gut itself. They found a decrease in inflammation and a roughly 30% decrease in I-FABP – a marker for leaky gut – in aged mice that received young fecal matter transplants. In contrast, young mice that received aged fecal matter had increased inflammation and a roughly 30% increase in I-FABP levels. These findings suggest that fecal matter transplants from young mice decrease inflammation and leaky gut in aged mice.

Previous studies have indicated that changes in gut bacteria have been associated with increased inflammation, and have been linked to issues with lipid metabolism such as dyslipidemia, atherosclerosis, and non-alcoholic liver disease. Parker and colleagues found shifts in the types of bacteria likely responsible for the changes in inflammation observed. Lipid synthesis and biosynthesis of B-vitamins (B7 and B9) were also found to be enriched in the aged mice following fecal matter transplants from young mice, and young mice who received aged fecal matter transplants had depleted lipid synthesis. Both lipid and B-vitamin synthesis are important for numerous cellular processes and reactions in the body, which may be changing as we age due to the age-related microbiota changes.

Improving Gut Microbiota to Reduce Inflammation

There are numerous studies indicating that the bacteria within our intestines change as we age, and there is increased intestinal permeability, or “leakiness”. Previously it was unclear which came first, the change in the bacteria or the gut leakiness. This study shows that age-related changes to our intestinal bacteria drive inflammatory changes throughout our bodies, including our eyes, brains, and yes, our intestines.

Back in 2017, there was interest as to whether changing one’s gut microbiome could affect one’s athletic performance. A consensus was never reached. But for now, it seems that age-related changes to our gut microbiome may affect inflammation within our bodies, now whether fecal matter transplants could become more commonplace as an anti-aging technique, well that’s up for debate as much more research is needed.

An easily observed practice that could benefit one’s gut health immediately would be adding probiotics to one’s diet, and possibly affecting the gut-brain axis in that way. Probiotics are commonly used for treating gastrointestinal issues like irritable bowel syndrome and can help restore the composition of the gut microbiota, benefit our gut health, and further prevent gut inflammation, which may ultimately prove to be beneficial to our aging bodies.