Key Points:

- Learning to play piano (P) and music culture (MC) — listening awareness without practice — for six months increases brain volume in several regions, including the cerebellum.

- P and MC improve memory, which is correlated with factors like time spent practicing and sleep duration.

- P but not MC prevents atrophy of the auditory cortex region of the brain.

It was once believed that older individuals could not learn new skills due to a lack of neuroplasticity — the ability of the brain to reorganize its structure to account for new or lost information. However, it has become increasingly clear that the brain remains at least somewhat plastic throughout a lifetime.

In support of this notion, researchers from the Geneva Musical Minds Lab in Switzerland report in Neuroimage: Reports that P and MC enhance brain gray matter and memory despite general brain atrophy in older adults. Marie and colleagues show that P and MC increase brain volume and improve memory, while only P prevents atrophy of the auditory cortex. Still, general atrophy of the brain occurs despite musical intervention.

‘‘A global brain pattern of atrophy was present in all participants. Therefore, we cannot conclude that musical interventions rejuvenate the brain. They only prevent aging in specific regions,’’ says Damien Marie, the lead author of the study.

Learning to Play Music Increases Brain Volume

132 healthy older adults (62-78 years of age) with less than six months of musical training across their lifetime participated in the study.

‘‘We wanted people whose brains did not yet show any traces of plasticity linked to musical learning. Indeed, even a brief learning experience in the course of one’s life can leave imprints on the brain, which would have biased our results’’, explains Marie.

The participants were separated into either the P group or the MC group. The P group learned piano, including how to perform piano pieces and read a musical score. The MC group controlled for enjoyment, social, and learning effects not related to playing an instrument. They were told not to create any type of music, even clapping and singing. Instead, they learned analytical music listening, like perceiving different instruments and music history.

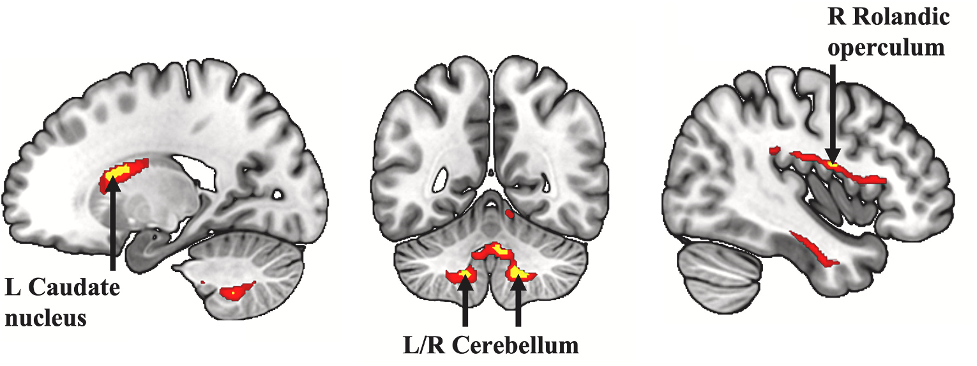

To assess brain volume and atrophy, Marie and colleagues measured brain gray matter from participant MRI scans. Gray matter consists mostly of the cell bodies of neurons, as opposed to white matter, which consists largely of axons. The results showed that whole-brain gray matter (GM) volume was not different between P and MC groups. However, after combining both groups, GM volume was shown to increase over six months in the neocortex, cerebellum, and other regions.

The left caudate nucleus is involved in goal-directed behavior, so brain volume increases in this area may benefit executive functions like inhibiting or monitoring certain behaviors, which usually decline with aging. The Rolandic operculum is involved in many different cognitive processes, but the authors argue that its increased volume could relate to better coupling of auditory perception and vocal cord movement.

The cerebellum — historically linked to fine motor control — is now known to play role in cognitive function, such as storing information about motor-related aspects of speech and tone. It is also involved in detecting the direction from which sound is coming. Furthermore, the cerebellum detects differences in timbre, which includes the ability to detect differences in sound between instruments. Thus, these capacities could be improved by increased cerebellar volume.

Listening to Music Enhances Memory, and Playing Piano Maintains the Auditory Cortex

Working memory (WM) involves memories that we temporarily store and update to accomplish a goal, the same as our computers random access memory, RAM. For example, we use WM to remember the directions we just learned from a stranger to find a gas station. You are also now utilizing WM to follow this article. Tonal WM is the ability to remember different tones within one’s WM.

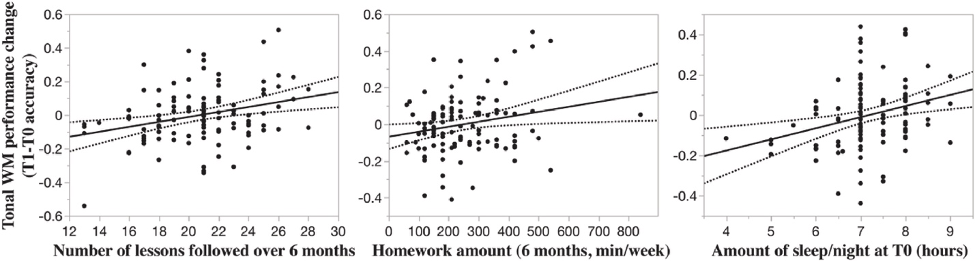

To assess tonal WM, Marie and colleagues had the participants guess given sequences of three tones while in the MRI machine. Based on correctly identifying the tone patterns, it was found that there was a 5.7% improvement in tonal WM performance with the P and MC groups combined. This improvement was correlated with increased GM volume, suggesting that these musical interventions improve WM by promoting neuroplasticity.

As part of the protocol, participants were given 1-hour long weekly music training lessons and told to practice at least 30 minutes at home for five days a week — homework. It was found that improvements in WM were positively correlated with number of lessons attended, time spent on homework (practicing) and sleep duration.

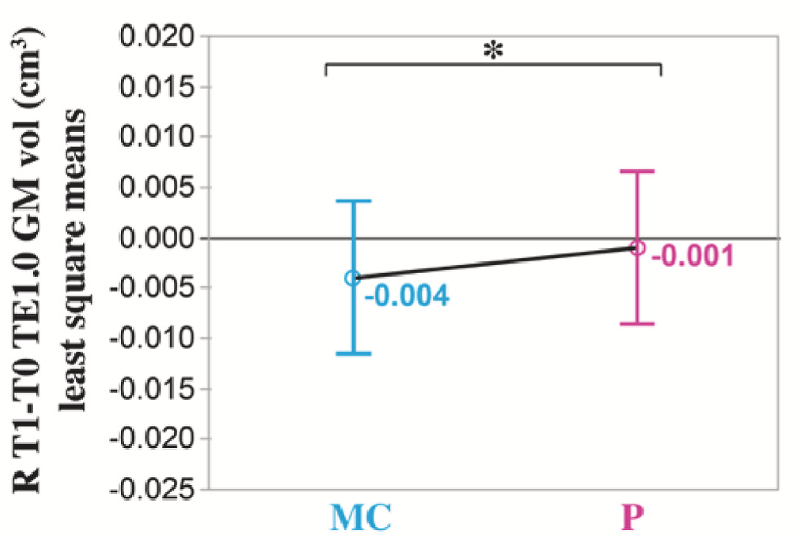

The primary auditory cortex is the region of the brain that processes hearing. Marie and colleagues found the GM volume of the auditory cortex remained stable in the P group while it decreased in the MC group. The authors postulate that GM maintenance from piano may relate to audio-motor coupling. That is, the association between sound and objects like tone to keyboard, pitch processing, and or ear training.

The brain is known to atrophy with age but Marie and colleagues are one of the first to examine which regions are most susceptible to degeneration. They found that both musical intervention groups showed a widely distributed pattern of atrophy, including the neocortex, which makes up a large portion of the brain, the hippocampi, which allow us to form memories, and the cerebellum. Total GM atrophy volume decreased by 0.17%. However, GM atrophy did not relate to WM performance, suggesting brain resilience.

“The current study is the first interventional study reporting such detrimental effects over only 6 months despite stimulating activities.”

Picking Up a Guitar or Just Learning How Listen Could Help

In addition to the findings of Marie and colleagues, previous research has shown that music interventions can slow cognitive decline. It is also known that lifelong musical practice protects against dementia, possibly due to increasing brain resilience.

“These results suggest that not only music education – music practice, active listening and possibly singing, can countervail cognitive decline and dementia and promote brain preservation in later life, but also that stimulating activities at a younger age may be beneficial…. So, prevention of cognitive decline should start way before getting old.”

For those of us who don’t want to invest in a piano, or any other instrument, based on this study, it seems that just learning how to listen to music can help with cognitive decline.