Key Points:

- Dementia prevalence in Tsimane and Moseten, two indigenous groups residing in the Bolivian Amazon, is among the lowest in the world.

- Physical endurance and cardiovascular fitness obtained from hunting and agricultural work likely contributes to improved cognitive health.

- Lack of high-fat diets and access to processed foods reduce the risk for cognitive impairment.

The prevalence of dementia around the world varies between populations, with certain countries bearing more societal health burdens than others. This has driven scientists to explore what’s behind these global disparities to better understand why humans experience cognitive impairment upon aging.

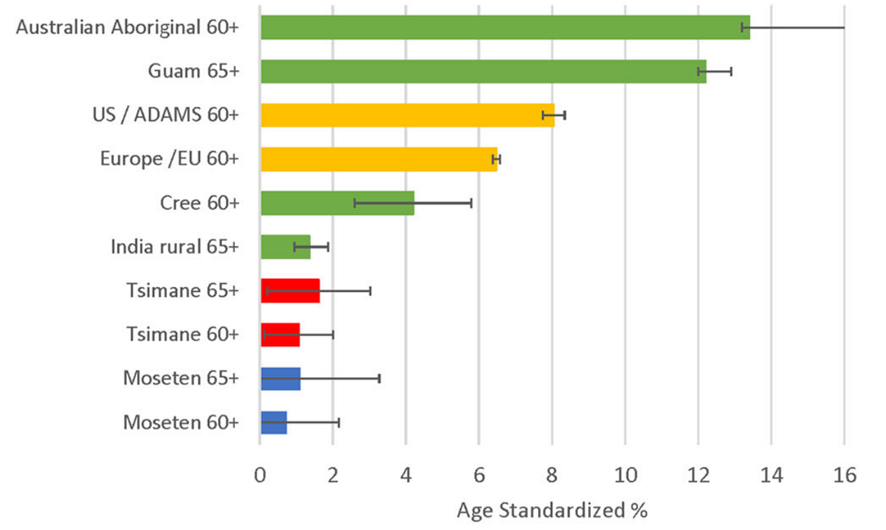

In a new study published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia, University of Southern California (USC) researchers along with international collaborators examined the prevalence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) among the Tsimane and Moseten indigenous groups, both of which are known to live subsistence lifestyles — the condition of just having enough resources to stay alive. Statistical analysis of subjects aged 60 and older revealed extremely low dementia prevalence among both indigenous groups, with only 1.2% of Tsimane subjects and 0.7% of Moseten subjects exhibiting dementia, which is almost ten times less than the 8% to 11% seen in older individuals living in high-income countries. Additionally, Gatz and colleagues found significantly low rates of MCI in Tsimane subjects (7.7%) and Moseten subjects (9.8%). Neurological evaluations also concluded that there were strong associations between MCI and Parkinsonian symptoms, problems with visual and spatial memory, and increased risk of heart disease.

How The Tsimane and Moseten Thwart Cognitive Impairment

Shockingly, nearly 40% of individuals aged 65 and older will experience some level of cognitive impairment, usually denoted by difficulties with memory, language, thinking or judgment. What’s more, statistics show that 5.2% of individuals aged 60 and older live with dementia globally, and experts suggest that this number will increase by 204% in the year 2050. With human aging being the primary catalyst of onset dementia, populations with low life expectancy tend to have diminished rates of dementia. However, certain lifestyle habits have been shown to mitigate cognitive impairments upon aging, and the Tsimane and Moseten indigeneous groups are two perfect examples of this.

“By working with populations like the Tsimane and the Moseten, we can get a better understanding of global human variation and what human health was like in different environments before industrialization,” says Benjamin Trumble, co-author of the study and associate professor at Arizona State University, in a press release. So, why do these two indigenous groups have some of the lowest global rates of dementia and cognitive impairment?

Their minimalist lifestyle is quite physically demanding, requiring optimal cardiovascular endurance to consistently hunt and farm without the assistance of industrial tools. Having good cardiovascular fitness has been repeatedly shown to increase longevity as well as reduce the risk of developing dementia. So, by avoiding physical inactivity, which is commonly seen in high income populations, both indigenous groups are able to maintain adequate physical fitness that boosts their overall health.

Diet has also been another avenue of exploration in combating memory deficits, with studies concluding that diets high in fat and refined carbohydrates – energy molecules that have undergone extensive processing and no longer carry the vital nutrients and minerals needed for proper cellular functioning – compromise the brain region linked to memory (hippocampus) and induce brain inflammation. With this in mind, both the Tsimane and Moseten indigenous groups lack access to these types of foods and, in turn, reap the benefits of eating naturally produced foods that contain essential nutrients. “Something about the preindustrial subsistence lifestyle appears to protect older Tsimane and Moseten from dementia,” states Margaret Gatz, USC professor of psychology and lead author of the study, in a press release.

Brain Composition Among MCI and Dementia Subjects

Cognitive decline is usually accompanied by changes in overall brain structure and composition. Thus, after Gatz and colleagues conducted brain scans and neurological evaluations to quantify dementia and MCI prevalence among the Tsimane and Moseten, they tried to identify any associations between cognitive impairment and altered brain composition resulting from living a subsistence lifestyle. Upon analysis, investigators found that brain images from MCI or dementia subjects exhibited brain arterial calcifications, defined by the buildup of plaque in arteries, that are known to contribute to neurological dysfunction and increased risk of heart disease.

However, while these calcifications were more prominent in MCI and dementia subjects, non-impaired participants also exhibited similar calcifications, highlighting the need for further research to fully comprehend the role of arterial calcifications in neurological diseases. Be that as it may, results showed a strong association between brain calcifications and increased risk of cognitive impairment. Moreover, the findings shed light on another potential target for the treatment of neurological disorders.

A previous systematic review of 15 indigenous populations across multiple continents revealed that dementia prevalence ranged from 0.5% to 20% among individuals aged 60 and older. When investigators proceeded to compare dementia rates from the Tsimane and Moseten to other indigenous or illiterate rural populations, the findings confirmed that the Tsimane and Moseten had the lowest prevalence of dementia. Interestingly, Gatz and colleagues posited that dementia prevalence among other indigenous populations may vary due to their integration with neighboring high income societies. While these integrations provide indigenous populations with access to critical resources like education and medicine, they ultimately become exposed to risks commonly faced in high-income societies like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, all of which are known contributors of dementia.

While it is highly unlikely that people from high-income countries will transition to the indigenous subsistence lifestyle simply to thwart cognitive decline, incorporating cognitive boosting habits such as increasing physical activity and avoiding processed foods or high-fat diets can still help limit the risk of MCI and dementia. Nevertheless, certain unavoidable risk factors like air pollution pose a continual threat to overall brain health and cognition. Granted that avoiding all cognitive-impairing agents is nearly impossible, and considering that aging inevitably increases people’s susceptibility to neurological decline, all we can try to do is live a balanced lifestyle conducive to healthy aging. In the meantime, scientists will continue searching for effective targeted therapeutics that will help attenuate this ubiquitous disease.