Key Points:

- TMS treatment led to a 52% reduction in cognitive decline.

- The treatment reduces loss of independence by 96%.

- Significant improvements in behavioral symptoms were also observed.

The results of a Phase II clinical trial, published in Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, reveal that 52 weeks of TMS treatment mitigates cognitive decline, independence loss, and behavioral disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. With no serious side effects associated with the treatment, this approach is more effective and safer than the drugs currently prescribed to AD patients.

TMS Reduces Alzheimer’s Progression

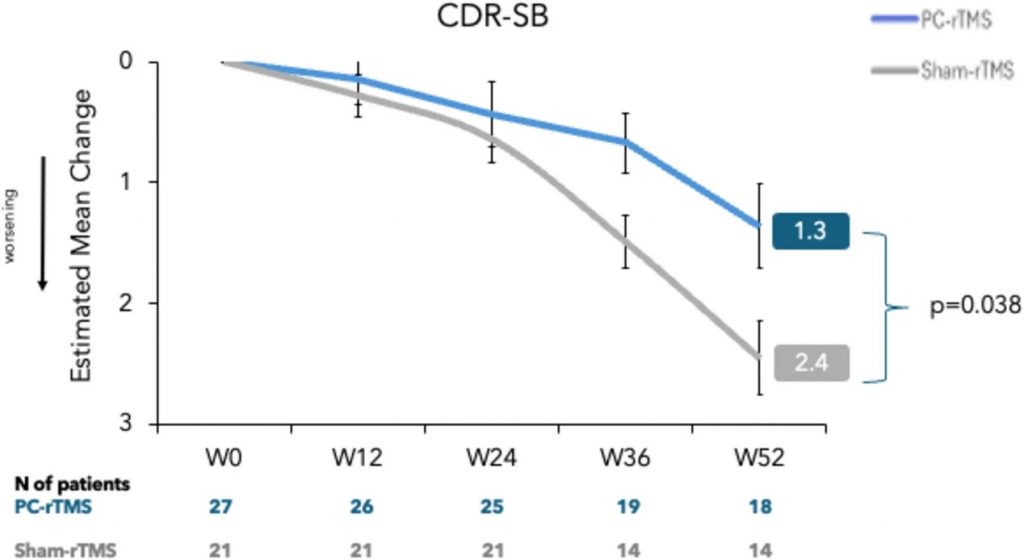

Over 52 weeks, expert neurologists and neuropsychologists periodically performed clinical evaluations on AD patients, blinded to whether each patient received the actual TMS treatment or a sham treatment. Cognition was measured with the CDR-SB (Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes), which scores dementia severity on a scale of 0 to 18. In this scheme, a score of 0 is normal, and a score of 18 suggests severe dementia. The results showed that while all participants showed worsening (higher) scores over 52 weeks, the TMS-treated participants showed significantly less worsening of cognition.

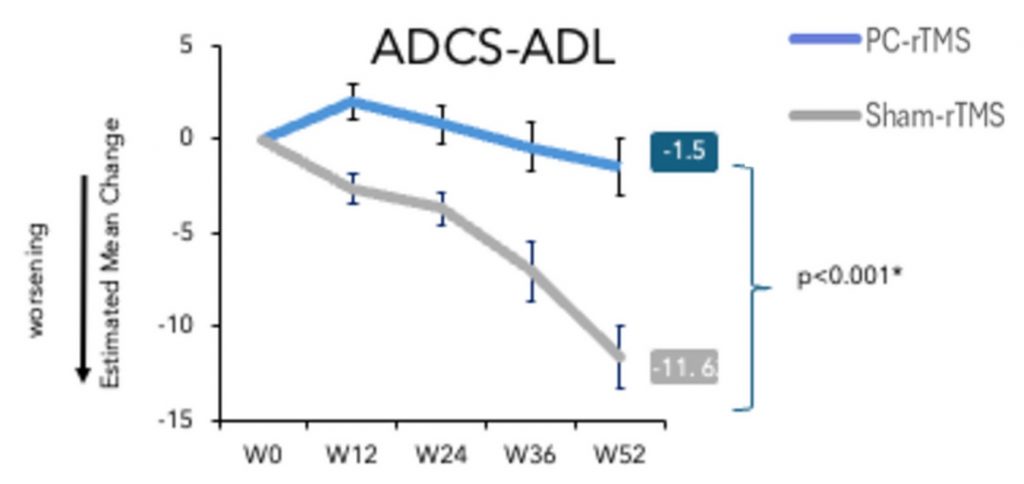

The research team, led by Italian neurologist and neuroscientist Dr. Giocomo Koch, evaluated the autonomy of the participants using the ADCS-ADL (Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living) scale. A lower score on the ADCS-ADL scale indicates less competence in daily living activities, such as eating, walking, and bathing. For instance, a score of 0 indicates that a given activity necessitates the help of a caregiver. Over 15 million caregivers, including family members and other unpaid Americans, spent an estimated 18 billion hours caring for AD patients in 2015 alone. With that being said, TMS treatment resulted in a 96% improvement in the participants’ ADCS-ADL scores, suggesting that TMS largely prevents loss of independence and, potentially, the need for caregiver support.

In another evaluation, the Italian researchers assessed behavior using the NPI (Neuropsychiatric Inventory), a questionnaire that asks about the presence and severity of specific behaviors, including delusions and hallucinations. With lower scores indicating better behavioral symptoms, TMS-treated participants showed significant improvements after 52 weeks. Improved behaviors included apathy, for which there are no pharmaceutical interventions. Apathy can hinder quality of life, worsen dementia severity, and increase caregiver burden.

“This publication reaffirms our confidence in the potential for our non-invasive precision neuromodulation therapy, nDMN, to slow the impairment of cognitive functions, preserve activities of daily living, and reduce behavioral disturbances in Alzheimer’s patients,” said, Dr. Koch, scientific co-founder of Sinaptica Therapeutics, the company that conducted the study. “We continue to build on our positive clinical evidence, including with a just-initiated Phase 2 study in Early Alzheimer’s patients, as well as ongoing preparations to launch a pivotal trial in Mild-to-Moderate patients.”

More Clinical Trials and Existing TMS Clinics

TMS is already approved for the treatment of several conditions, including treatment-resistant depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). With many scientists across the world testing TMS on AD patients in clinical trials, it may only be a matter of time before AD is approved. Dr. Koch and Sinaptica are said to begin Phase III trials in 2025, involving 300 participants.

TMS clinics can be found all over the world. In the United States, a single session of TMS therapy can cost up to $500 per session or up to $15,000 for 36 sessions. Moreover, these clinics may one day offer AD therapy if clinical trials continue to show positive results and the FDA approves.

How Does TMS Affect the Brain?

With TMS, magnetic coils generate a local electric field that crosses the cranium and activates the electrical activity of neurons in the brain. When a neuron is stimulated repeatedly, it initiates the formation of new synaptic connections through a process called LTP (long-term potentiation). It is thought that TMS restores LTP, which has been shown to be disrupted in AD patients.

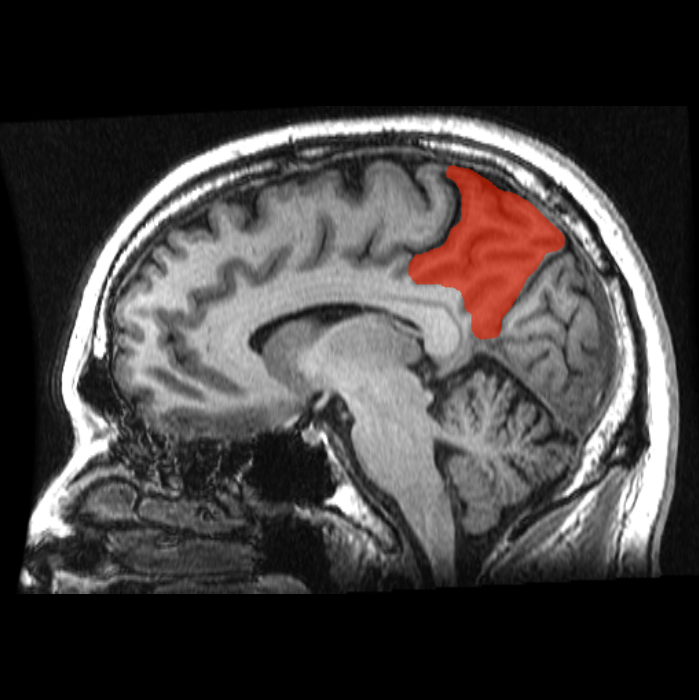

Dr. Koch and his team stimulated an area of the brain particularly susceptible to degeneration called the precuneus. The precuneus integrates information from many regions of the brain and is one of the most highly connected “hubs” of the brain. Likely due to increased metabolic demand, hubs like the precuneus are vulnerable to deterioration, leading to neurodegenerative diseases, brain tumors, and psychiatric disorders. As such, the precuneus is the earliest brain region to be affected by AD pathology, including connectivity disconnection.

The precuneus is part of the DMN (default mode network), the dysconnectivity of which was recently shown to predict whether an individual would develop dementia. The DMN produces our inner mental lives and plays a direct role in self-reference, social cognition, language, and memory (episodic, autobiographical, and semantic memory). Thus, as the DMN becomes disconnected in AD, these cognitive processes gradually decline. It follows that TMS may improve cognition and behavior in AD patients by restoring DMN connectivity via LTP.