Key Points:

- Three years of metformin supplementation via drinking water slows cognitive loss in older monkeys.

- Metformin reduces age-associated senescent cells in multiple organs, including the brain.

- The researchers say metformin acts by activating a protein called Nrf2, which is like a master antioxidant switch.

Our brain helps us to learn and remember information that helps us navigate reality and interact socially. When our brains age, our ability to learn and remember declines. However, certain anti-aging compounds may slow this decline. One of these compounds is metformin, and scientists have recently found it to improve learning and memory in older male cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis), with implications for humans.

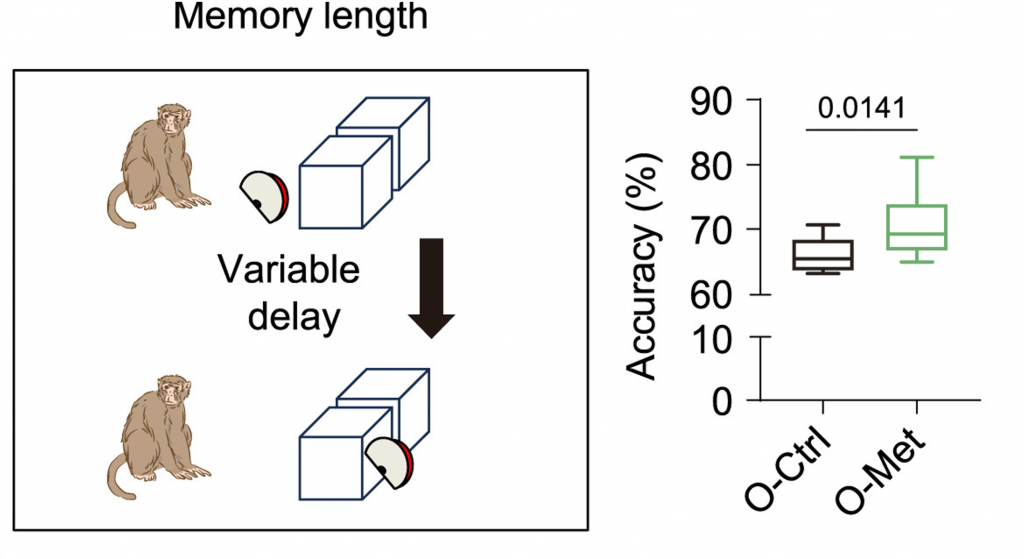

Measuring Memory in Monkeys

To measure brain aging in monkeys, researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences used the monkeys’ innate desire for food. The monkeys were presented with food, which was then covered by one block, while another block was used to cover no food. Then, after a short delay, each monkey had to remember which of the two blocks covered the food. It was found that the monkeys given 20 mg/kg/day of metformin more accurately chose the correct block, suggesting metformin improves short-term memory.

Similar tests involving blocks and food were used to determine that metformin improves learning and cognitive flexibility — adapting one’s thinking to changing environments. Furthermore, MRI scans revealed that metformin prevented brain deterioration, as measured by frontal lobe cortical thickness. The frontal lobe is a brain region associated with planning, problem solving, learning, memory, and other higher cognitive functions, suggesting metformin improves memory by preserving this area of the brain.

Indeed, metformin was shown to enhance neuronal regeneration and synaptic connectivity, which is important for neuronal plasticity. When we learn new things, our brain uses neuronal plasticity to form new memories. Additionally, in a brain region important for consolidating memories known as the hippocampus, there were fewer brain immune cells called microglia in metformin-treated monkeys. Microglia are implicated in neurodegenerative diseases and aging. These findings suggest that metformin preserves the brain at the cellular level by protecting against the adverse effects of aging, including brain inflammation and deterioration.

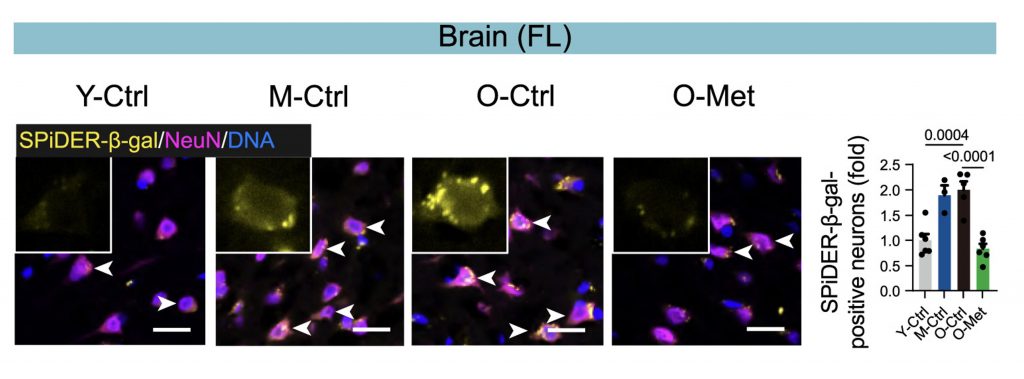

Removing Pesky Senescent Cells and Slowing Aging

Several hallmarks of aging, which are underlying biological causes of aging, have been identified, including senescent cells. When senescent cells accumulate, they promote inflammation and organ deterioration, potentially driving the aging process. In metformin-treated monkeys, the researchers found fewer senescent cells in organs such as the lung, liver, kidney, heart, stomach, skin, and brain. They also showed that metformin led to a reduction in pro-inflammatory and pro-organ-deteriorating molecules secreted by senescent cells called SASP factors.

Other hallmarks of aging were also attenuated by metformin treatment, such as organ scarring (fibrosis) and inflammation. Furthermore, the age-related reduction in type II muscle fibers was counteracted by metformin, suggesting it can delay muscle aging. Additionally, biological age — age determined by changes in gene activation and other measurements — was reduced in metformin-treated monkeys. These findings demonstrate, by multiple measures, that metformin slows the aging process in older monkeys.

Metformin Does Not Slow Aging by Lowering Blood Sugar?

Metformin treats type 2 diabetes in humans by lowering blood sugar. However, the researchers found that metformin had a minimal effect on blood sugar levels in the older monkeys. This is expected, considering that animals did not have diabetes. Instead, based on their experiments, the researchers say that metformin reduces neuron senescence and slows brain aging by activating a protein called Nrf2. Nrf2 plays a major role in fighting against oxidative stress, a hallmark of aging.

Slowing Human Brain Aging

The researchers point out the applicability of their study to humans, saying,

“The metformin dosage in our primate study falls within the standard therapeutic range, enhancing the applicability of our findings to human therapeutics. The observed reversal of aging biomarkers in primates indicates the feasibility of targeting core aging mechanisms in organs, offering a strategy to improve chronic conditions and prevent age-related diseases.”

Whether metformin can slow brain aging in healthy older humans remains an open question. This is why the Chinese Academy of Sciences researchers in Beijing, led by Dr. Guang-Hui Liu have launched a 120-person clinical trial to test the effects of metformin on aging. Moreover, Dr. Nir Barzilai, a researcher at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, is trying to raise $50 million to run a 3,000-person clinical trial. Thus, we may know whether metformin can mitigate human aging in the near future.

Notably, there is one way to activate Nrf2 without drugs. Regular exercise activates Nrf2, which contributes to the cardiovascular benefits of exercise, including mitochondrial health and reduced artery plaque buildup (atherosclerosis). The older monkeys were housed in a room and not systematically exercised, suggesting that their lifestyle may have potentially diminished Nrf2 activation levels, compared to if they were in their natural environment.

Exercise has repeatedly been associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality and incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in humans. Exercise also helps to modulate blood sugar levels and lower the risk of type 2 diabetes. Therefore, while metformin may potentially slow brain aging in sedentary individuals, it may not do so in physically active individuals. If trying to slow brain aging, exercise (encompassing both cardiovascular and resistance training) is more likely to do so than metformin or any other compound.