Highlights:

- Older adults with high muscle fats have the most improvements in physical performance in response to resistance exercise, independent of muscle size.

- Metformin blocks increased strength gained by resistance exercise in non-diabetic older adults with high muscle fats.

- Older adults who improved the most in response to resistance training had the highest levels of muscle cell recomposition.

As early as the age of 40, our muscles start to shrink and become weaker. With each year, the size and strength of our muscles decline more and more rapidly. So far, the best way to prevent muscle decline is with resistance exercise, such as weightlifting, but this only works for 60-75% of older adults. Some studies even show that some older adults lose muscle and strength in response to resistance exercise, but why some older adults respond better than others to resistance training is unclear.

By analyzing data from their previous clinical study (NCT02308228), called the Metformin to Augment Strength Training Effective Response in Seniors (MASTERS), Long and colleagues from the University of Kentucky in Lexington showed that older adults with high muscle fats benefit the most from resistance exercise. In the study published in GeroScience, the researchers also showed that the type-II diabetes drug metformin negated many of these benefits. To that effect, whether taking metformin or not, older adults with low inner muscle fats responded the least to resistance exercise.

Low Muscle Fats Are Linked to Increased Physical Performance

Not only do muscles dwindle with age, but fat also accumulates within and around them, like the marbling of a steak. These muscle fats (lipids) have dire consequences and alter strength, balance, and walking speed. Long and colleagues are the first to study the effect of muscle fats on responsiveness to resistance exercise in older adults.

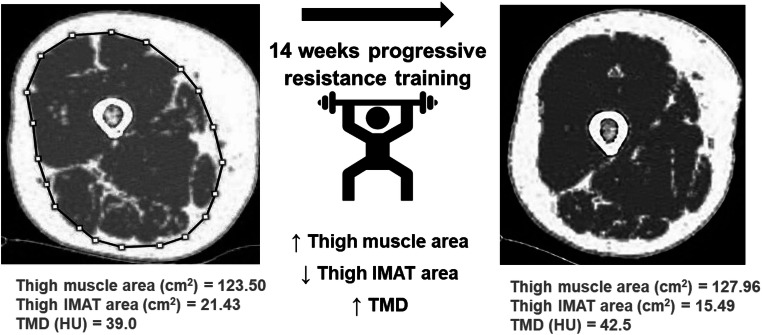

To begin, the Kentucky researchers took a “before picture,” or “baseline,” of each participant in the study, who were high functioning individuals 65 years of age and older. The “before picture” included measurements of muscle fats and physical performance. Then, after resistance exercise training, the measurements were repeated.

Long and colleagues assessed physical performance by various measures, including balance and walking speed. They evaluated the strength and power (strength multiplied by speed) of each participant with repeated chair stands (sitting down and standing up from a chair), as well as weightlifting exercises. The participants were also asked to assess their own physical function and performance.

By analyzing the relationship between muscle fats and physical performance, Long and colleagues found that older adults with low inner muscle fats had increased strength and power before resistance training. For the elderly, this is important because strength and power are vital in performing daily tasks, which improves the quality of life.

Older Adults with High Muscle Fats Benefit the Most from Resistance Training

There are several possible reasons why some older individuals do not respond to resistance exercise. Long and colleagues proposed that high levels of outer muscle fats were one of these reasons. However, after the participants performed resistance exercise for 14 weeks, the researchers found no association between outer muscle fats and increased muscle size and strength.

Because high outer muscle fats did not seem to affect resistance training responsiveness, Long and colleagues looked at participants with high inner muscle fats. They found that the older adults with high inner muscle fats had more significant improvements in physical performance in response to resistance training, suggesting that inner muscle fats are more important than outer muscle fats when it comes to resistance exercise.

Metformin Reduces Strength Gains in Response to Resistance Training

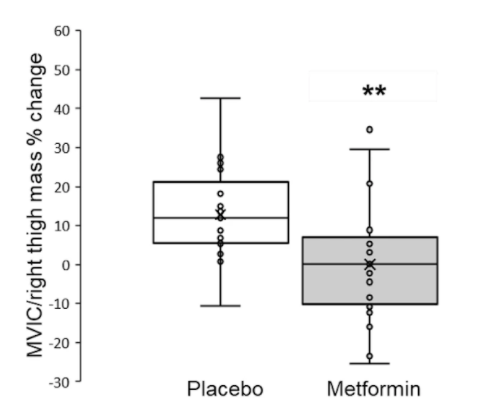

Because type-II diabetes affects about 25% of older individuals and metformin is the most prescribed medication for people with diabetes, Long and colleagues tested the effect of metformin on responsiveness to resistance training in half of the participants. They found that metformin reduced strength gains in older adults with high inner muscle fats.

However, the authors point out that the participants in this study were healthy individuals without type-II diabetes. Also, the evidence varies on the degree to which metformin affects different aspects of physical performance in people with diabetes. Therefore, studies examining changes in muscle fats in response to resistance training in people with diabetes are needed.

Muscle Composition Could be More Important than Muscle Size

Long and colleagues predicted that increased muscle size would increase physical performance, but this was not the case. So, they took muscle samples from the participants to examine their muscle composition before and after resistance training.

The Kentucky researchers found that performance gains were associated with increased larger, strength-related type 2 fast-twitch muscle cells, which have less fat than the smaller, endurance-related type 1 slow-twitch cells. These findings suggest that muscle composition (increased type 2 muscle cells) may be more important for performance gains than muscle size in older adults. To support this, metformin, which reduced performance gains, also reduced the increase in type 2 muscle cells.

Is there a Limit to our Performance Potential in Old Age?

Overall, Long and colleagues showed that older adults with low inner muscle fats respond the least to resistance exercise. Since decreased inner muscle fats were associated with changes in muscle composition, the older adults who didn’t respond to resistance training may have had less potential for muscle recomposition. What determines the potential for muscle recomposition remains an open question but may result from previous exercise experience. While the participants included in the study had not exercised regularly for one year, exercise experience in the years before may have influenced muscle cell-type composition.

This study hasn’t been the only one showing that metformin may negate the positive effects of exercise. A related study using the MASTERS clinical data underscored that metformin negatively impacts the hypertrophic response to resistance training in healthy older individuals. Another clinical study showed that metformin inhibits mitochondrial adaptations to aerobic exercise training in older adults. These data suggest that before prescribing metformin to slow aging, we need additional studies to understand how metformin elicits positive and negative responses with and without exercise.