Circadian rhythms—physiological changes that follow a daily cycle, like the sleep-wake cycle—get disrupted as we get older, which can contribute to the development of age-related diseases. However, the mechanisms and signals linking circadian rhythms and aging are unclear.

A research team from Northwestern University published an article in the journal Molecular Cell showing that the molecule nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) controls circadian rhythm signals and can prevent age-related declining circadian function in mice. They found that boosting NAD+ levels restores youthful gene activation and rhythms of activity in the cell’s powerhouse, the mitochondria, in old age. These findings reveal that NAD+ has a major role in influencing both behavior and metabolic health.

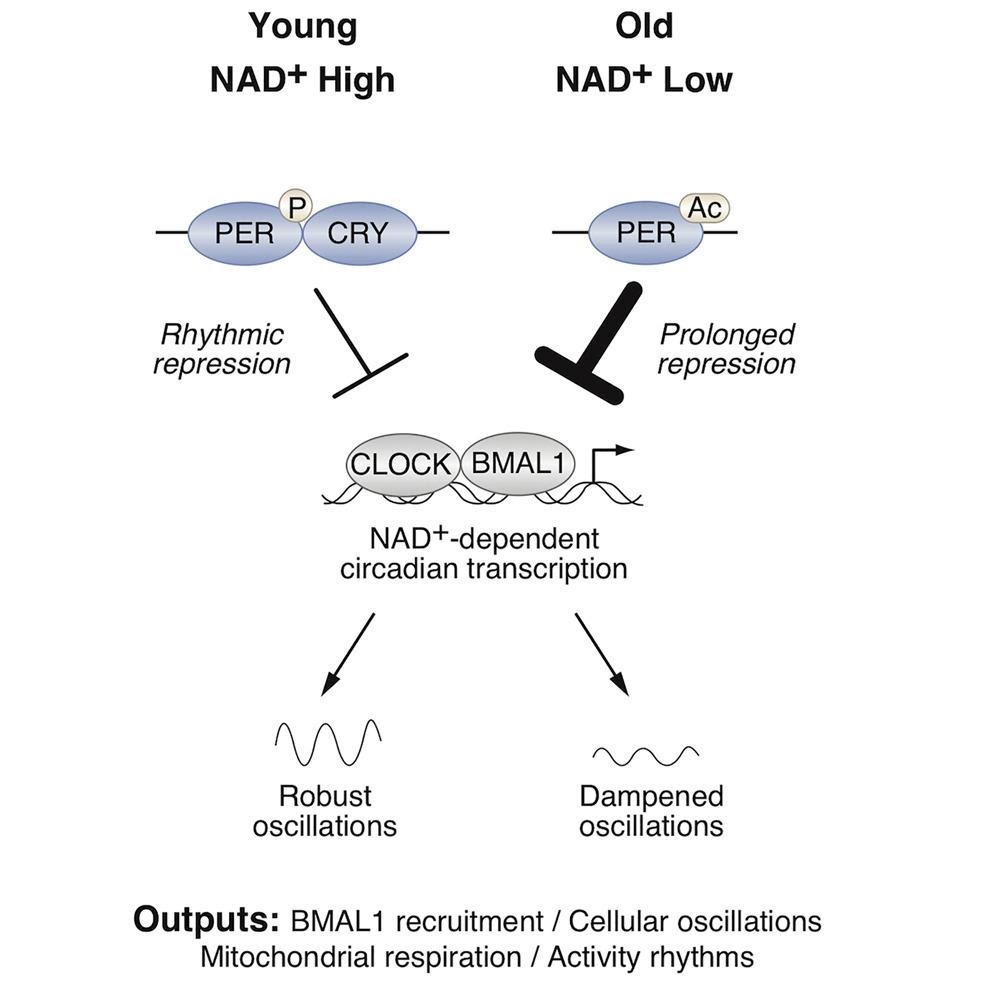

NAD+ levels in our cells decline as we age. However, it has been shown that boosting NAD+ production by supplementing with its precursors promotes youth in mice. NAD+ is necessary for the function of sirtuins—proteins known for promoting healthspan and lifespan. A member of this family of enzymes called Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) regulates circadian rhythms by binding to members of the “core clock complex,” which consists of gene activators CLOCK–BMAL1 and the gene repressor PER2. To do so, SIRT1 modulates PER2 by a process called deacetylation, which leads to the degradation of PER2 and activation of specific genes related to the circadian rhythm.

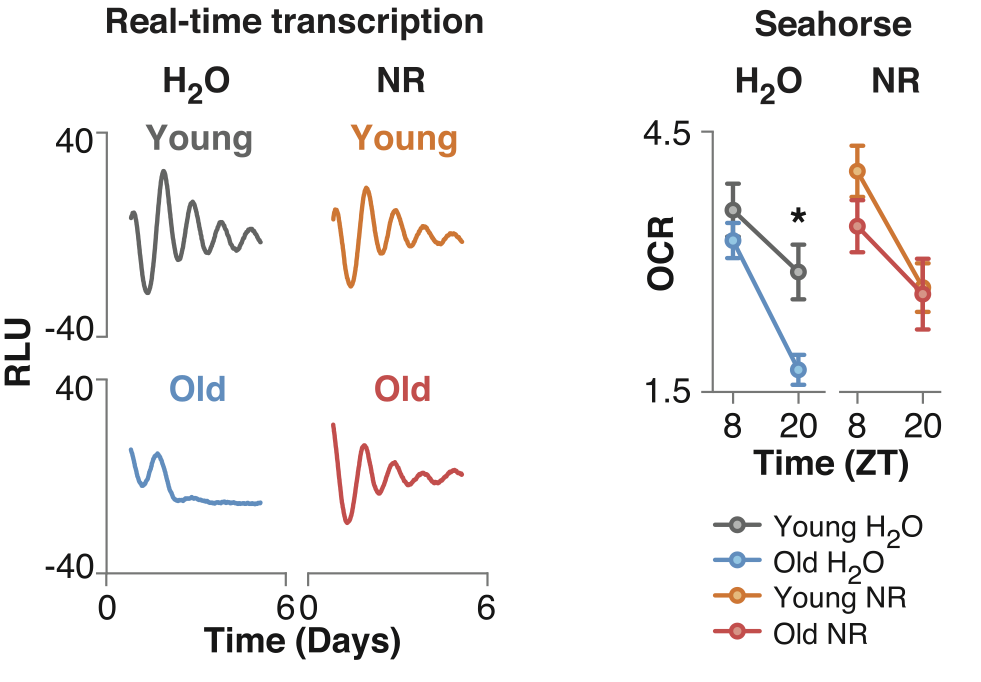

To investigate the role of NAD+ in circadian gene expression in mice, the researchers gave mice drinking water supplemented with NAD+ precursors, specifically nicotinamide riboside (NR), for four months and then analyzed how genes related to circadian rhythms were activated in the liver. This revealed that the activation pattern of roughly half the circadian-regulated liver genes changed after increasing NAD+. “Our observation that NR supplementation exerts broad effects on rhythmic gene transcription in liver and our identification of NAD+ as a regulator of SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of PER2 establishes a mechanism by which NAD+ regulates the clock,” said the investigators.

When the investigators increased NAD+ levels with NR supplementation, it enhanced the function of the circadian gene activator BMAL1 in mouse livers and increased the activation of the circadian rhythm gene. On the contrary, when the investigators eliminated SIRT1 from the liver in mice, it eliminated the changes in circadian rhythm gene activation in the liver that were observed when NAD+ levels were increased. This showed increased NAD+ levels improve circadian rhythm through a mechanism dependent on SIRT1.

Moreover, the localization of PER2 in the nucleus, which is where it acts to repress genes linked to circadian rhythms, was increased in cultured SIRT-1 deficient cells. Also, when the investigators depleted NAD+ in mice, they observed increased modifications of PER2 that promote its stability and activity as well as its retention in the nucleus and, therefore, its functionality. Altogether, NAD+ curbs PER2 activity as a circadian gene repressor and thereby increases circadian gene activation through BMAL1. This shows that NAD+ promotes gene activity controlled by BMAL1 through SIRT1 and PER2.

Next, the investigators found that the BMAL1 function in the liver of old mice was decreased, which coincided with increased PER2 levels and reduced the circadian gene oscillation intensity. When the investigators administered the NAD+ precursor NR to the old mice for 6 months, they observed restored BMAL1 function to levels similar in young animals.

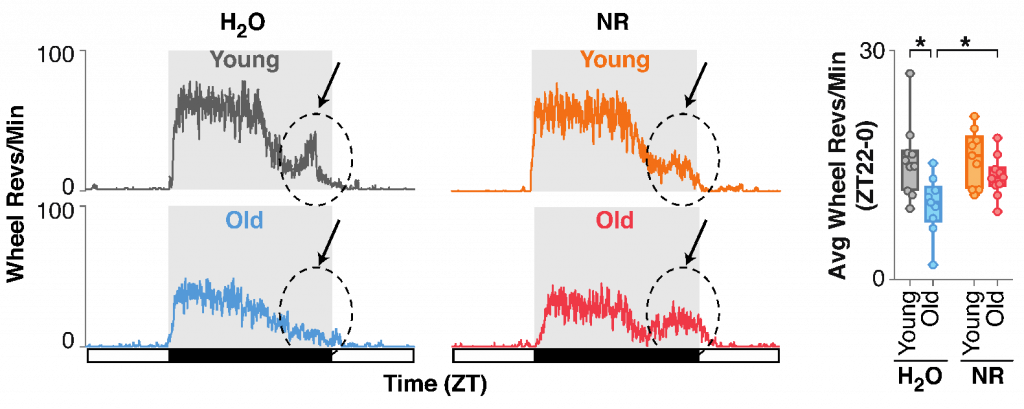

When they administered NR, the amount of late-night physical movement, which is normally reduced in old mice, was restored to youthful levels. “Provision of NR…in drinking water of old mice countered the decline in nighttime locomotor activity rhythms,” said the investigators.

In summary, increasing NAD+ can reverse aging-associated circadian rhythm dysfunction. Correcting circadian rhythmicity with NAD+ could also be examined for circadian rhythm disorder management linked to PER2 deregulation, such as those caused by shift work or mutations in PER2. “Our studies clarify the mechanisms underlying SIRT1-mediated regulation of the clock, for which discrepant mechanisms were previously proposed,” said the investigators.