Key Points:

- Older adults with mildly high cholesterol levels have a greater chance of survival than older adults with lower cholesterol levels.

- Cholesterol levels were measured only once, which doesn’t account for fluctuations over long periods.

- Cholesterol can be lowered by diet, exercise, or NAD+ precursors.

Cholesterol has become demonized due to its association with heart disease, making statins — cholesterol-lowering pharmaceuticals — the hero. However, some studies, particularly of older adults, have shown that cholesterol may not be the enemy. Recently, researchers from Italy discovered that people with higher cholesterol levels live longer than people with lower cholesterol levels.

High “Bad” Cholesterol Prolongs Survival

To study the relationship between cholesterol and lifespan, researchers analyzed individuals from Sardinia, Italy. Sardinia is one of five regions in the world where many people have lived for more than 90 years. These regions are called “Blue Zones,” and the other four are in:

- Okinawa, Japan

- Loma Linda, California

- Nicoya, Costa Rica

- Ikaria, Greece

The study included 168 individuals between the ages of 90 and 107 who had four grandparents from the Italian Blue Zone.

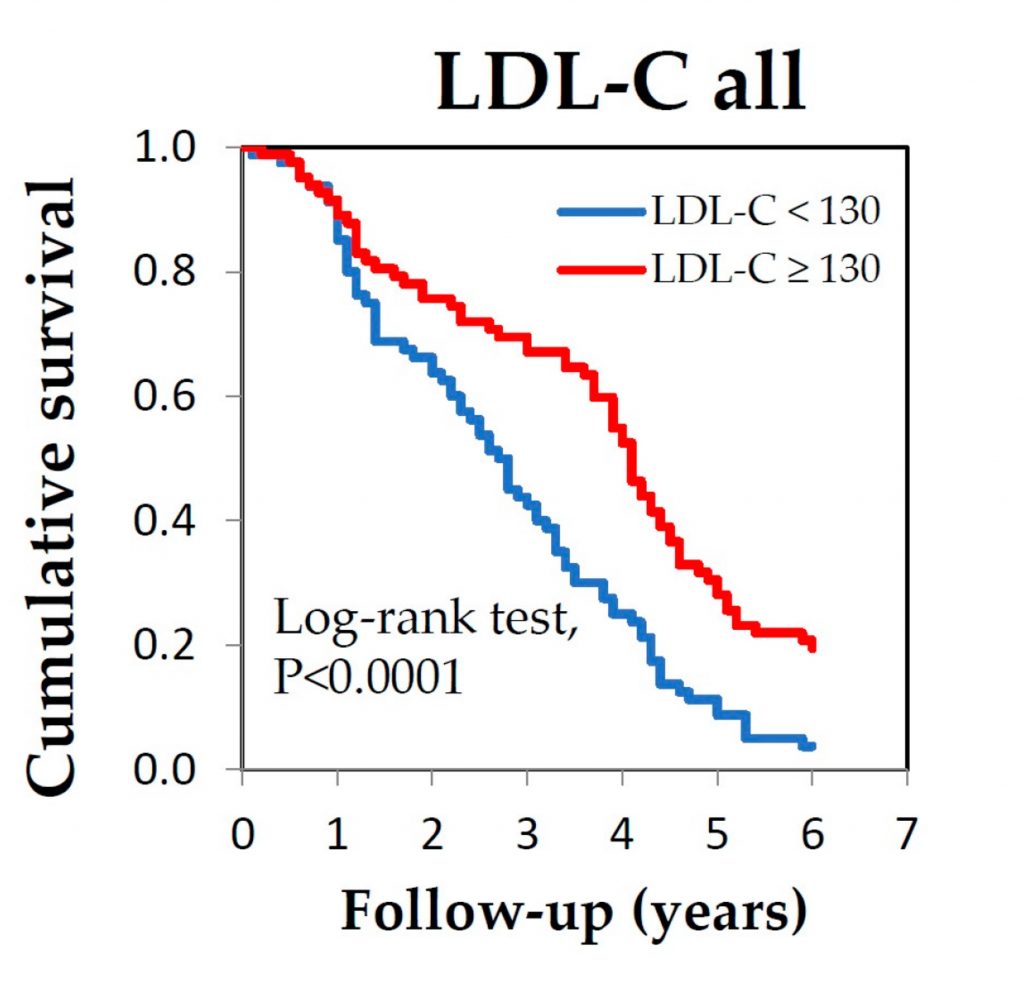

After an overnight fast, blood samples were taken from participants to measure their cholesterol levels. Based on their LDL cholesterol (“bad” cholesterol) measurements, the participants were divided into two groups: one group had cholesterol levels below 130 mg/dL and the other had cholesterol levels at or above 130 mg/dL. Notably, an LDL cholesterol level of 130 mg/dL is considered mildly high while 100 mg/dL is considered healthy.

The researchers kept track of the participants over six years until all but 20 had died. With death records in hand, the researchers calculated which group of participants lived longer on average. The results showed that the group with cholesterol levels at or above 130 mg/dL had a higher chance of living longer than the group with cholesterol levels below 130 mg/dL. These findings call into question whether high LDL cholesterol levels are a risk factor for fatal heart diseases, particularly in really old people.

Bad Study Design?

A major limitation of this study is that cholesterol levels were only measured once. The participants were then followed over the course of years without any additional measurements. It’s possible that, over the course of years, the LDL cholesterol levels of the participants did not remain constant, but fluctuated. If blood samples were taken, for example, every six months, a more accurate assessment of the participants’ cholesterol levels over time could have been made.

Several lifestyle factors can influence our LDL cholesterol levels, including diet, exercise, and stress. In this study, when the blood samples were taken, the participants filled out a questionnaire to roughly assess their diets for the previous year. The researchers used this information to find a correlation between higher levels of cereal consumption and higher LDL cholesterol. However, the consumption of cereals and other foods could have changed during the course of the study.

The participants were also asked how often they engage in physical activity, which could influence LDL cholesterol levels. The results showed that 85% of males and 69% of females engaged in physical activity more than three times a week. However, the type and duration of physical activity was not specified. Also, physical activity level assessments were made only once and could have changed over six years.

Overall, if the study included more frequent assessments of dietary patterns and exercise levels, along with more frequent blood sample measurements, the results could be explained more easily. That is, the reason for individuals with higher LDL cholesterol having a greater chance of survival would potentially be clearer.

Modulating LDL Cholesterol to Live Longer

High LDL cholesterol levels, particularly in middle-aged adults, are associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis, a condition where plaques clog the arteries. Atherosclerosis is the leading cause of death in the United States. While statins are commonly prescribed to lower LDL cholesterol levels, they come with side effects such as muscle aches and pains, fatigue, and dizziness. To avoid side effects, it may be advantageous to lower LDL cholesterol levels naturally by making specific lifestyle choices.

Diet

Most Americans do not consume enough fiber, which plays a critical role in lowering LDL cholesterol levels. A meta-analysis of 181 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed that for every 5 gram increase in soluble fiber intake, there is more than a 5 mg/dL decrease in LDL cholesterol. Foods high in fiber include mostly fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds, and grains. For example, avocados, raspberries, pears, broccoli, peas, lentils, almonds, chia seeds, and oats are good sources of fiber.

Consuming foods high in cholesterol, such as eggs does not raise LDL cholesterol levels, at least not due to the cholesterol. In response to dietary cholesterol intake, the liver can reduce cholesterol synthesis, reduce intestinal cholesterol absorption, and increase cholesterol excretion, thereby regulating blood cholesterol levels. However, some individuals harbor a genetic risk for absorbing more cholesterol from food and should watch their cholesterol intake.

Saturated fat raises blood LDL cholesterol by inhibiting LDL receptors and increasing the synthesis of LDL particles. Notwithstanding the debate over whether saturated fat leads to heart disease, most experts agree that saturated fat intake should be limited. Saturated fat is found in mostly animal-based foods, such as meat, butter, yogurt, and cheese. Some plant-based products, including coconut and palm oil, also contain saturated fat. Saturated fat-containing butter and oils are almost always an ingredient in cakes, cookies, biscuits, pastries, and other baked goods.

Exercise

A meta-analysis of 148 RCTs showed that exercise lowers LDL cholesterol by 7.22 mg/dL on average. Exercise also increases “good” HDL cholesterol, which plays a protective role against heart disease. A meta-analysis of 15 RCTs found that neither aerobic, resistance, nor combined exercise is more effective at lowering LDL cholesterol levels, suggesting any type of exercise is suitable for lowering LDL cholesterol. Exercise may lower cholesterol by increasing its utilization by our muscles and increasing its excretion.

NAD+ Precursors

NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) precursors are molecules that elevate NAD+ levels, which tend to decline with age. NAD+ precursors include NMN (nicotinamide mononucleotide), nicotinamide riboside (NR), niacin, and nicotinamide. A meta-analysis of 40 RCTs showed that NAD+ precursors, particularly niacin, lower LDL cholesterol. Moreover, 1 gram of NMN has been shown to lower LDL cholesterol in overweight and obese middle-aged adults. NAD+ may lower cholesterol by improving cellular energy metabolism.