Key Points:

- Rapamycin reduces muscle size and strength in young rats when compared to untreated rats consuming the same amount of food.

- Many longevity interventions are not meant to be taken at a young age.

- Alternatives to rapamycin may potentially include resistance exercise.

Rapamycin — an FDA-approved drug originally prescribed to prevent organ transplant rejection — has become one of the most well-known drugs associated with longevity (living longer). This is because multiple studies have shown it prolongs mouse lifespan, the gold standard of longevity supplements and drugs. However, a new study shows that rapamycin may diminish muscle size in younger individuals. The study reveals that caloric restriction — eating less food — is more beneficial.

Caloric Restriction More Beneficial Than Rapamycin

To determine the health effects of rapamycin on the young, researchers from the Nagoya Institute of Technology in Japan examined rats that were 11 weeks old, roughly equivalent to 20 human years. The results showed that, likely because it is associated with suppressing appetite, rapamycin caused the rats to eat less food. For this reason, the researchers fed a group of untreated rats the same amount of food consumed by the rapamycin-treated rats.

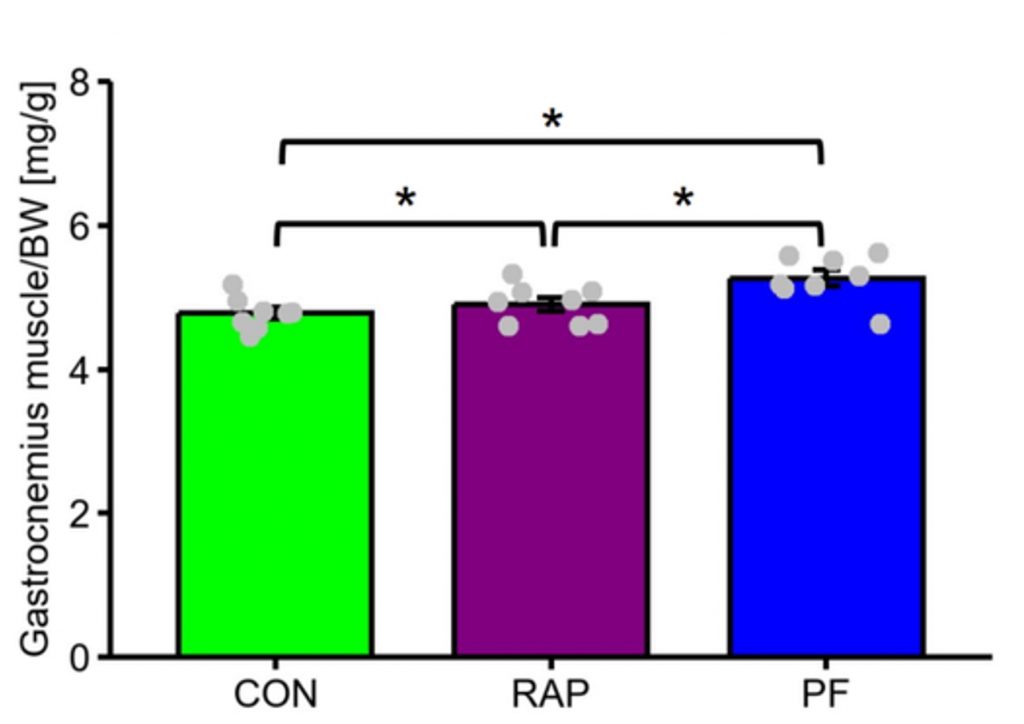

Despite eating less food, the rapamycin-treated rats had higher blood glucose levels than the untreated rats. The rapamycin-treated rats also had smaller calf muscles and smaller muscle fibers. Additionally, contractile force, an indicator of muscle strength, of rapamycin-treated rats was lower than that of the untreated rats. These findings suggest that, in young rats, consuming fewer calories alone is more beneficial to muscle health than consuming fewer calories while taking rapamycin.

Interestingly, a second group of untreated rats that ate normally had smaller calf muscles than the rapamycin-treated rats and similar strength levels. For this reason, more studies will be needed to determine the effect of rapamycin treatment on young rats that eat normal amounts of food.

When to Supplement with Longevity Interventions

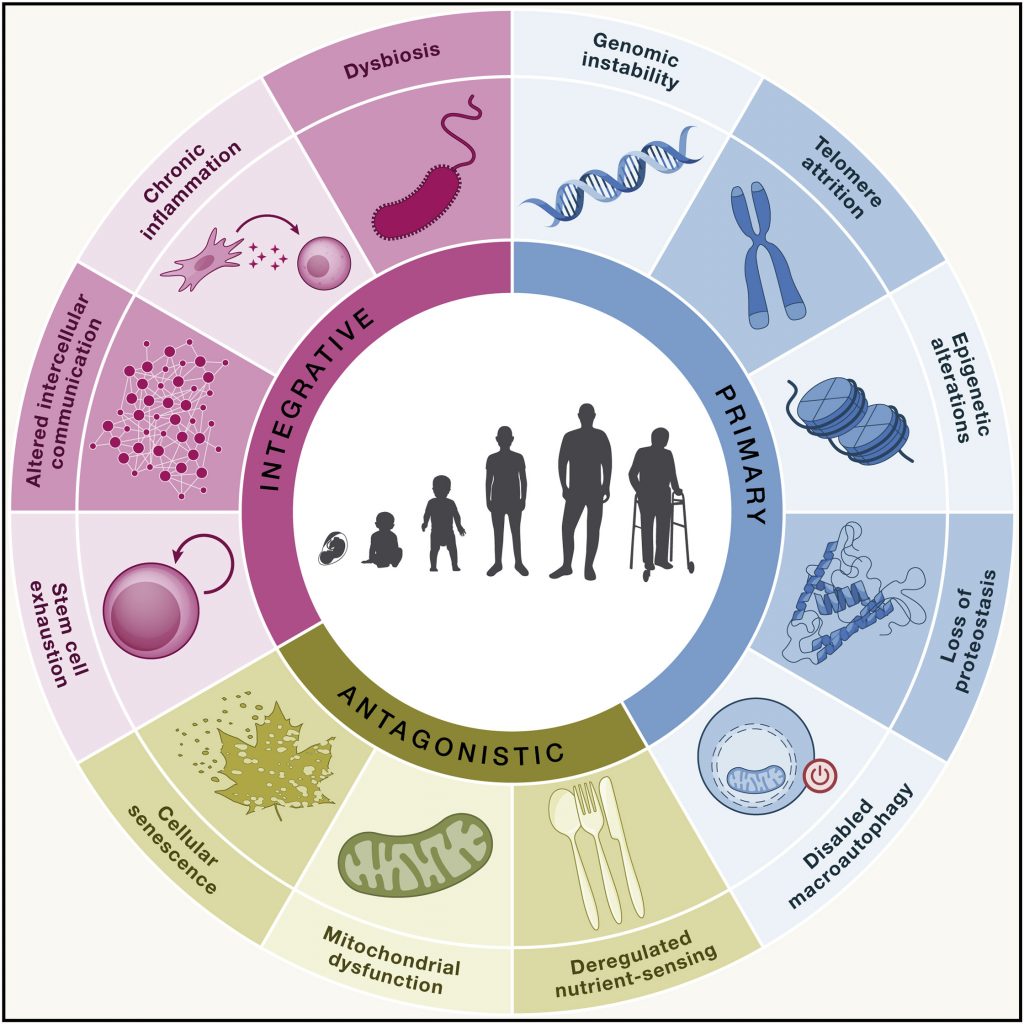

Current theories of degenerative aging suggest that, after a certain age, our cells gradually change in a deleterious manner. These changes result in chronic diseases, such as heart disease, neurodegeneration, or cancer, leading to an untimely death that could have been delayed in the absence of such a chronic disease. Many longevity interventions, particularly supplements and drugs, target these cellular changes that drive chronic diseases and aging.

The age-related cellular changes that drive aging include deregulated nutrient-sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, and disabled macroautophagy — our cellular waste disposal and recycling system. However, these changes may not occur until middle age or later in generally healthy individuals who are not obese. For example, impaired macroautophagy may not begin until the age of 38. Thus, taking rapamycin, which has been shown to promote autophagy, before age 38, may not be advantageous in this case. On the other hand, consuming too many calories and being sedentary can accelerate aging, which may impair macroautophagy earlier in life. This is why taking longevity supplements or drugs may be advantageous to obese individuals.

Alternatives to Rapamycin

While many studies have shown that rapamycin extends the lifespan of mice when the drug is administered after middle age, a previous study has shown that when rapamycin is administered to young mice, it stunts their growth. This is likely because rapamycin inhibits mTOR, a nutrient-sensing molecule that promotes growth. Through mTOR inhibition, rapamycin could also potentially inhibit growth, including the growth of muscles.

Considering the unwanted side effects of rapamycin, an alternative longevity intervention could be exercise. One study showed that exercise reduces diet-induced mTOR activation. Moreover, exercise counteracts high blood glucose levels. Also, studies show that exercise promotes macroautophagy like rapamycin. However, more studies are needed to determine the age-dependent effects of exercise on mTOR activation and inhibition and how this is modulated by rapamycin treatment.