Key Points:

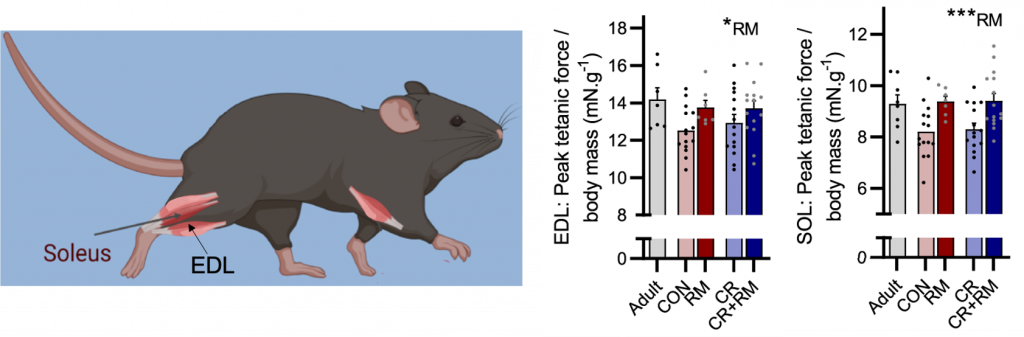

- Direct stimulation of muscle to measure strength is enhanced by rapamycin but not caloric restriction (CR).

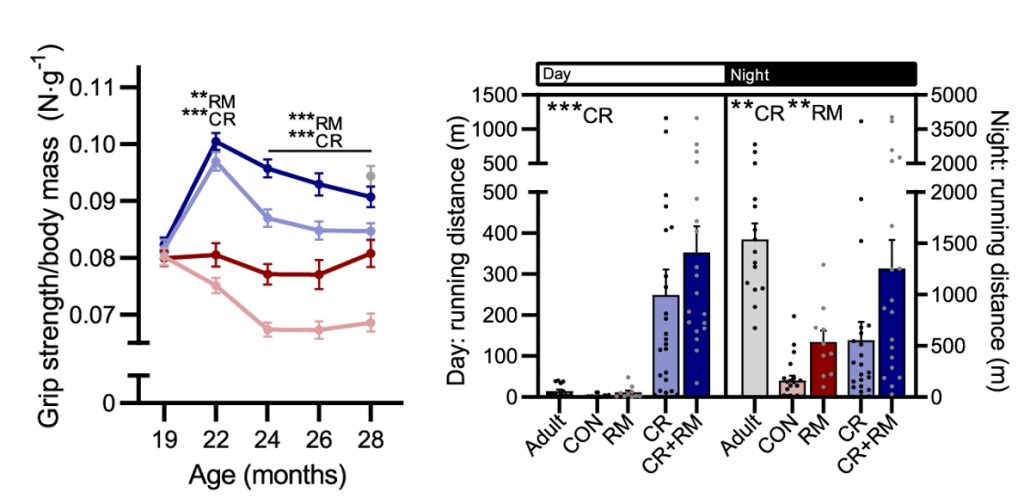

- CR and rapamycin synergistically enhance grip strength and running distance in aged mice.

- Genes associated with muscle growth are increased by rapamycin but further decreased by CR.

An often overlooked aspect of aging is a decline in muscle mass and strength. If we want to maintain our walking speed, ability get up from a chair, and prevent falls, keeping our muscles strong should be a priority. While animal studies consistently demonstrate the anti-aging benefits of dietary or calorie restriction (CR), it’s unclear whether CR is good for aging muscle. Rapamycin — a prescription drug that inhibits the nutrient signaling protein mTOR — has been touted as operating much like CR, leading to the same benefits. However, a new study shows that this is not the case when it comes to aging muscle.

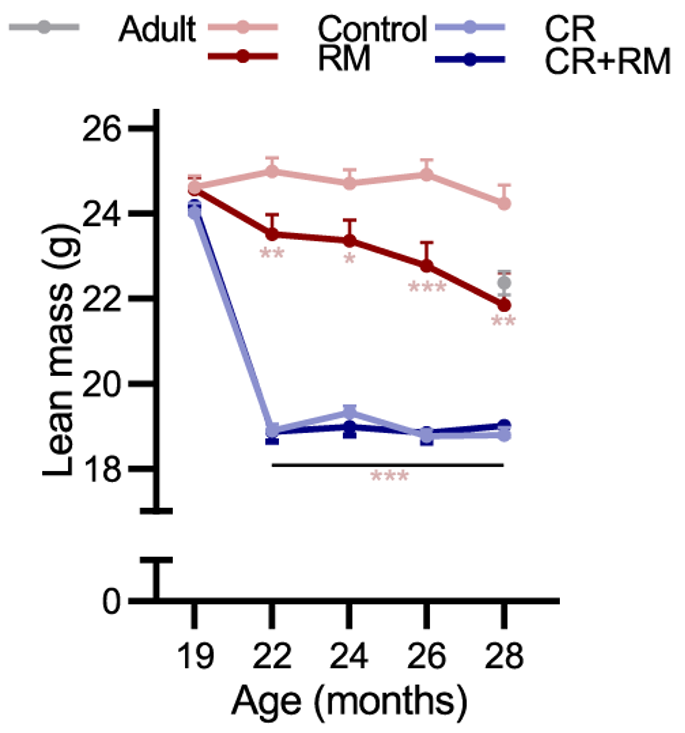

In Nature Communications, Ham and colleagues from the University Basel in Switzerland showed that with aging, CR and rapamycin have differential and synergetic effects on muscle strength and physical activity. They showed that rapamycin but not CR restores muscle strength when measured directly. They also showed that CR and rapamycin work synergistically to enhance grip strength and increase running distance. Additionally, Since CR causes a stark reduction in muscle mass, this study calls into question the utility of CR for preventing the age-related decline in muscle mass and strength.

Rapamycin Prevents Age-Related Muscle Weakenss

In mice, muscle strength can be measured in several ways, including by direct muscle stimulation, which bypasses the nervous system and cannot be influenced by the mental/emotional state of the mouse. Using direct muscle stimulation, Ham and colleagues measured the strength of aged mice (over 70 years old in human years)treated with rapamycin, aged mice on a CR diet, or aged mice treated with rapamycin and on a CR diet. They found that rapamycin treatment alone or with CR, but not CR alone restored the muscle strength of aged mice back to levels similar to the strength of middle-aged mice (about 50 years old in human years)

Ham and colleagues also measured grip strength, which may be a less reliable indicator of muscle strength than direct muscle stimulation because it does not bypass the nervous system. The Swiss scientists found that rapamycin and CR had a synergistic effect, preventing the age-related decline in grip strength. A similar effect was shown with voluntary running distance at night. That is, while rapamycin and CR increased grip strength and running distance alone, combining them had an additive effect.

Next, Ham and colleagues measured differences in muscle gene activation between rapamycin and CR in aged mice. Aside from both CR and rapamycin activating genes associated with reducing inflammation, most other age-related genes changed in the opposite direction (i.e., genes activated by CR were deactivated by rapamycin and vice versa). Notably, genes related to increased muscle size, known to decline with aging, were restored by rapamycin but further reduced by CR. These changes in gene activation reveal that rapamycin does not mimic CR at the genetic level.

A previous study compared the effect of rapamycin and CR on brain aging in mice to find a significant overlap in gene activation. The genes involved suggested that both rapamycin and CR could similarly slow down or reverse brain aging by improving brain function. These results are supported by another study showing that rapamycin improved spatial learning in middle-aged mice, although this was not compared to CR. Overall, these animal studies suggest that while rapamycin and CR have similar effects on brain aging, they don’t have the same effects on muscle aging.

Is Caloric Restriction a Good Idea for the Elderly?

An important finding in this study, as it pertains to humans, is that CR, even when combined with rapamycin reduced overall lean mass significantly more than rapamycin alone.

This is important because many older individuals suffer from sarcopenia, the age-related decline in muscle mass and strength.

“Age-related muscle decline already occurs in our thirties but begins to accelerate at around 60. By age 80, we have lost about a third of our muscle mass,” says Dr. Daniel Ham, one of the lead authors of the study. “Although this aging process cannot be stopped, it is possible to slow it down or counteract it, for example through exercise.”

Since many elderly individuals cannot afford to lose additional muscle mass, it may be critical to consume sufficient nutrients to limit muscle loss on CR. Alternatively, rapamycin could be taken for its potential strength-increasing benefits without the harm of significant reductions in muscle mass.

Preventing Age-Related Muscle Loss

As mentioned above, muscle decline begins as early as thirty years of age. This means that preventative measures can be taken to slow down age-related muscle decline. These preventative measures could include CR, but as mentioned above, CR is not the easiest intervention to uphold for extended periods of time. Therefore, in addition to building muscle with resistance exercise, rapamycin could possibly be used for preventing age-related loss in muscle strength. Of course, clinical research is needed to back this up.