Key Points:

- Due to age-related inflammation, nervous system aging is like the slow and gradual version of autoimmune diseases where the immune system attacks the nervous system.

- An age-reversal technology called cellular reprogramming counteracts inflammation-induced neuron death and senescent cells — cells that contribute to aging.

We age because our organs stop working, and our organs stop working because our cells stop working. Our cells stop working for many reasons, chief among them being chronic low-grade inflammation. Aging is characterized by inflammation accompanied by cell dysfunction, organ dysfunction, immune system decline, and age-related diseases. The term “inflammaging,” describing the inflammation that naturally occurs with aging, symbolizes the prominent role of inflammation in aging.

Inflammation causes damage to all organs, but unlike our skin, intestines, and liver, most of our nervous system cannot readily regenerate cells. When neurons die, particularly in the central nervous system, they can be difficult or impossible to replace. Inflammation can damage our nervous system by causing neuron death, a predicament that supports the development of neurodegeneration. Inflammation plays a crucial role in neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, an age-related disease that ranks among the top leading causes of death.

Senescent Cells Precipitate Inflammation

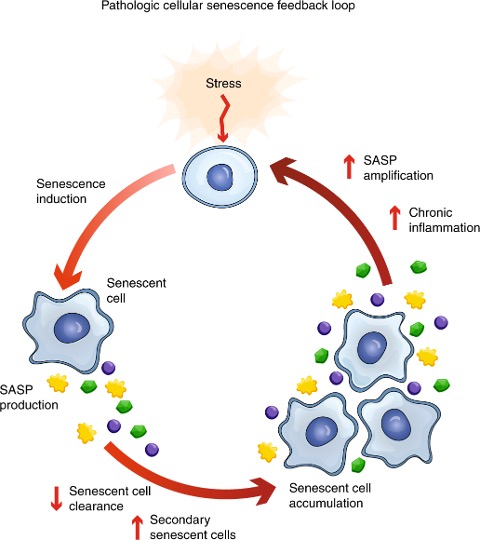

Senescent cells are a significant contributor to chronic low-grade inflammation. They produce a host of molecules known as the SASP (senescence-associated secretory phenotype), which include pro-inflammatory molecules called cytokines. With various stressors triggering the conversion of otherwise normal cells into senescent cells, these inflammation-promoting cells can appear anywhere in our body.

As we age, senescent cells accumulate in our tissues and organs, evading clearance from our immune system. This accumulation is exacerbated by some SASP factors triggering senescence in surrounding cells and cells of distant organs. In turn, secondary senescent cells further contribute to chronic inflammation. Moreover, inflammation itself is a senescence-inducing trigger, sustaining a vicious feedback loop that supports the accumulation of senescent cells.

Inflammatory Disorders Accelerate Aging

In a recent study published in Cell Reports, researchers, including those from Harvard University like David Sinclair, demonstrate similarities between nervous system aging and autoimmune diseases where the immune system attacks the nervous system. The researchers compared neurons from aged mice to neurons from a mouse model for autoimmune encephalomyelitis (AE), a disorder where inflammation damages the brain and spinal cord. They found that both aged neurons and AE neurons had similar genetic profiles, including an increase in senescent cell genes.

Moreover, the AE neurons had a similar profile to neurons from patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), another autoimmune disorder whereby inflammation damages neurons. Many of these similarities included biological drivers of aging like senescence, DNA damage, and mitochondrial dysfunction. The findings reveal that nervous system autoimmune diseases like AE and MS share many of the same underlying defects as the aging nervous system. Thus, some experimental treatments for AE and MS can potentially treat nervous system aging by reducing inflammation.

The Answer to Age-Related Inflammation?

Many therapies on the market can help alleviate inflammation, including compounds called senolytics, which remove senescent cells. However, a potential future therapy called partial cellular reprogramming may do more than just alleviate inflammation. Reprogramming, which involves exposing cells to transcription factor genes that rejuvenate cells, has been shown to prolong the lifespan of naturally aged mice by 109%.

The transcription factor genes that David Sinclair and his team use for reprogramming are called Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 (OSK). The OSK genes have previously been shown to promote neuron survival and optic nerve regeneration in mice. The OSK technology works by restoring the gene programs of cells to earlier stages of development, which can reverse senescence and inflammation. The OSK genes are administered through viral delivery systems, namely adeno-associated virus (AAV), which utilizes viral machinery without causing infections.

OSK Gene Therapy Protects Against Neurodegeneration

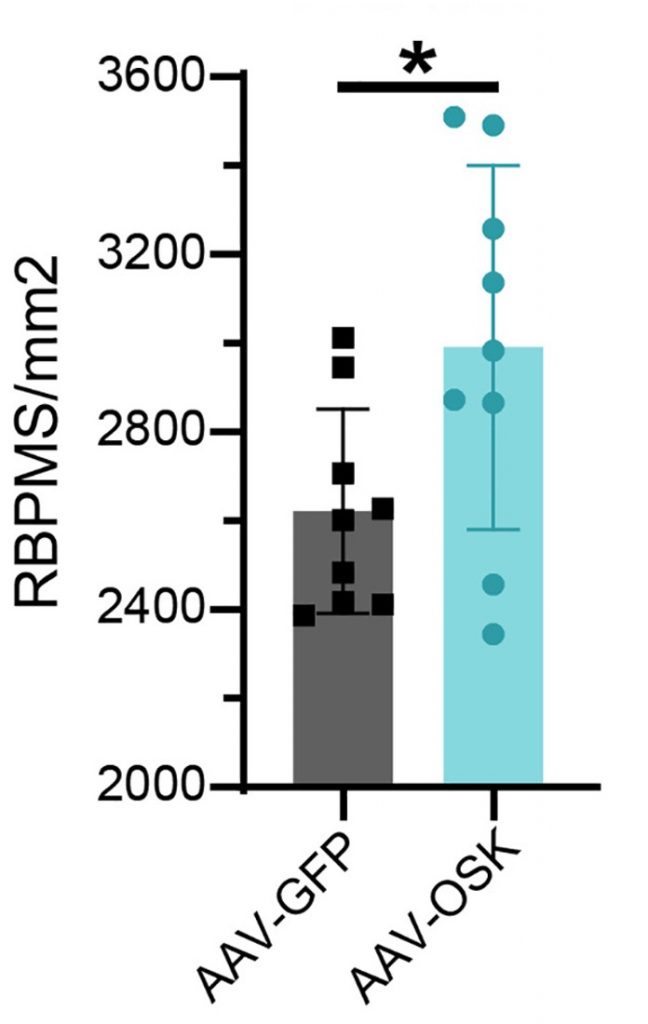

To determine the effect of OSK gene therapy on inflammation, Sinclair and collaborators injected AAV vectors carrying the OSK genes (AAV-OSK) into the eyes of AE mice. Remarkably, this improved the visual acuity of the mice and reduced the number of dead neurons in their eye. The neurons measured were retinal ganglion cells, which are the neurons that form the optic nerve and are necessary for vision. Indeed, the increase in retinal ganglion cells was correlated with improved visual acuity. These findings show that AAV-OSK gene therapy can protect against inflammatory AE and counteract neuron death.

Furthermore, upon measuring gene changes, the researchers found that AAV-OSK gene therapy counteracts genes involved in senescence. The AAV-OSK gene therapy was also shown to help prevent the deterioration of the nucleus, which is a marker for senescent neurons. Additionally, the gene changes showed that AAV-OSK therapy improves autophagy, our cellular waste disposal and recycling system that promotes longevity and counteracts neurodegeneration. Neuroplasticity and learning genes were also improved by AAV-OSK therapy, suggesting that reprogramming can potentially combat cognitive decline and dementia.

Will OSK Gene Therapy Work on Humans?

Scientists like Charles Brenner, PhD, do not think that OSK gene therapy will ever go into clinical trials because the Institutional Review Board (IRB) won’t allow it. The IRB oversees the welfare of human subjects and decides whether experiments are ethical. Brenner argues that reprogramming will inevitably lead to tumor growth, making it impossible to get past a reasonable ethics committee. While there are studies showing that reprogramming does not cause tumor growth, he argues that the researchers who conducted these studies did not look hard enough for tumors.

Only time will tell if Brenner is correct. It’s also possible that OSK gene therapy can be refined so that it does not lead to tumor growth. Of course, more animal studies will be needed to test this, and researchers will have to ensure that people like Brenner think they have searched properly for the tumors.