Key Points:

- Dutch scientists performed an updated analysis of an ongoing worldwide Amyloid Biomarker Study, now consisting of 19,097 participants with varying degrees of cognition.

- The analysis shows a 10% increase in the proportion of non-demented individuals who have detectable levels of the Alzheimer’s biomarker amyloid.

- The APOE ε4 gene and education level were associated with higher levels of amyloid in all populations studied, with an age-dependent caveat for the AD population.

- Australia had the highest amyloid levels in the AD population, but not all continents were studied.

We don’t want to think that a sticky, toxic protein called amyloid has accumulated in our brain, increasing our risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative disorders. If we don’t notice any signs of cognitive impairment – difficulty remembering, learning, and making decisions – why should we? However, new research suggests that more of us could have this AD biomarker in our brains without noticing.

As reported in JAMA Neurology, Jansen and colleagues from Maastricht University in the Netherlands show that while the prevalence of amyloid has stayed relatively constant over the years in adults with AD, there is an increased prevalence of amyloid in adults without dementia. These findings indicate that more individuals are at risk for AD than previously estimated, which can be a major socioeconomic burden if gone unchecked.

Amyloid Biomarker Study

As part of a 2013 initiative called the Amyloid Biomarker Study, Jansen and colleagues pooled data from 85 amyloid-related studies conducted in North America, Europe, Australia, and Asia. Their analysis involved separating the combined 19,097 participants into four groups based on results from cognitive tests or self-assessments: normal cognition, cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, and clinical AD.

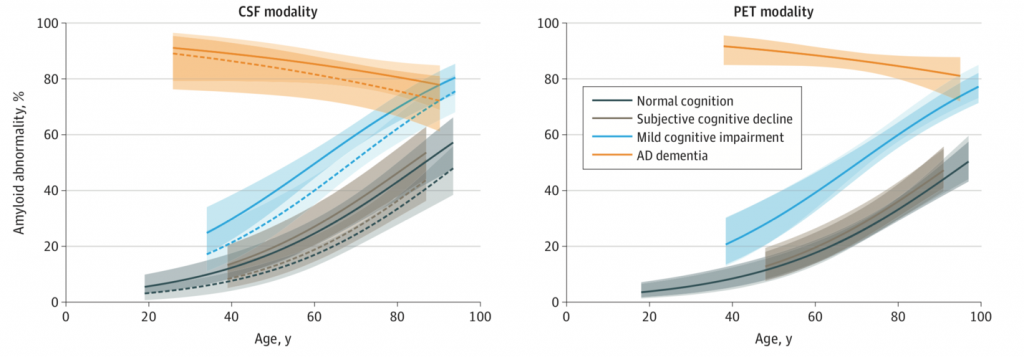

The Dutch researchers compared two methods for detecting amyloid: 1) PET (positron emission tomography) which uses a radioactive tracer to detect amyloid protein in the brain, and 2) spinal fluid, which contains metabolites from the brain, including amyloid.

AD Risk Higher in Elderly Adults without Dementia

Jansen and colleagues first analyzed participants without dementia: normal cognition (passing cognitive test score), cognitive decline (self-assessed cognitive impairment but passing test score), and mild cognitive impairment (less severe version of AD based on test score). Their initial analysis gave results that were similar to the previous 2015 analysis.

In all three non-dementia groups, amyloid prevalence increased with older age. Like before, participants with normal cognition and cognitive decline had similar levels of amyloid. Also, like the previous study, participants with mild cognitive impairment had higher amyloid levels than participants with normal cognition and cognitive decline.

But, after adjusting the statistics based on the more precise spinal fluid amyloid measurement, the results changed. The spinal fluid measurements gave a 10% higher estimate for amyloid than the PET measurements. This means that AD risk, as indicated by amyloid prevalence, is 10% higher than previously estimated for individuals with normal cognition, cognitive decline, and cognitive impairment.

“These patterns imply that at least during the early stages of AD and before dementia onset, [spinal fluid] may be a more sensitive marker of amyloid accumulation than PET,” wrote Christina Young and Elizabeth Mormino of Stanford University in an editorial written on Jansen and colleagues report in JAMA Neurology.

(Jansen et al., 2022 | JAMA Neurology) Spinal Fluid Measurements Show Amyloid Prevalence Higher in Non-Demented Individuals. Prevalence of amyloid based on cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) measurements (left panel) and PET measurements (right panel). With spinal fluid measurements, amyloid prevalence is higher in individuals with normal cognition, cognitive decline, and mild cognitive impairment.

Genetic Risk Factor

In addition to comparing differences in amyloid prevalence between spinal fluid and PET measurements, Jansen and colleagues compared other known risk factors for AD using the more accurate statistical parameters they derived from the spinal fluid amyloid measurements.

APOE (apolipoprotein E) ε4 is the gene most highly associated with AD risk. Jansen and colleagues found that, with both PET and spinal fluid amyloid measurements, carriers of this gene had higher levels of amyloid at an earlier age. This applied to all four levels of cognitive impairment, confirming that APOE ε4 increases the risk of AD.

Education Level

Regardless of age, amyloid measurement method, or APOE ε4 status, Jansen and colleagues found that higher education level was associated with a higher prevalence of amyloid in participants without dementia. For the participants with AD, this was true at the age of 60 but not above the age of 60. The association between higher amyloid levels in individuals with higher education but without dementia can be explained by increased levels of cognitive reserve – an increased resistance to cognitive decline and impairment.

Geographical Region

For the participants without dementia, Jansen and colleagues saw no differences in amyloid prevalence across regions. For the participants with AD, the prevalence of amyloid was higher in Australia compared to Europe, Asia, and North America, although there was less data from Australia.

Christina and Elizabeth wrote “It is alarming that a large-scale effort that examined the data of more than 19,000 individuals and characterized them by PET or [spinal fluid] measures was not positioned to report the role of race and ethnicity or the proportion of individuals composing various racial and ethnic groups to give a sense of the cohort’s demographic characteristics and generalizability of findings.”

Indeed, the dataset excludes individuals from entire continents, including Africa and South America. Therefore, whether the results of this study reflect the true prevalence of amyloid in all corners of the world is unknown. In addition to missing valuable ethical and racial data, the study also does not consider socioeconomic status, which may also prove valuable, since some studies have shown that socioeconomic status has an influence on AD prevalence.

Biomarkers for Disease Prevention

Based on Jansen and colleagues’ analysis, spinal fluid measurements may be more precise than PET measurements for estimating the prevalence of amyloid, especially in younger age groups and individuals with normal cognition. As amyloid measurements become more precise, it may be possible to detect very low levels of amyloid in more individuals and at earlier ages.

While improving the accuracy and precision of spinal fluid and PET measurements for amyloid will be beneficial, honing in on other methods for measuring AD biomarkers may be more beneficial. For example, while they have yet to reach clinical use, blood-based biomarkers seem more practical. Spinal fluid measurements can be invasive and PET scans can be expensive, making them difficult to administer at large scales. The acquisition and analysis of blood samples is already integrated into the global healthcare system, making blood-based biomarkers an accessible and easy to implement method for detecting AD risk.

Biomarkers like amyloid are not only associated with AD but other diseases like Parkinson’s disease and diabetes. Based on reliable biomarkers like amyloid, preventative measures can be taken before these diseases reach the clinical stage. The problem is that it is difficult to prevent disease without knowing the cause. And, at least in the case of AD, we don’t know exactly what causes this devastating neurodegenerative disorder. Therefore, research focused on understanding the causes of AD are needed to make the best use of biomarkers like amyloid.

A study published in 2021 projected that the number of people with clinical AD will climb from about 6 million to about 14 million by 2060 in the United States alone. This means that if a preventative treatment or strategy for AD is developed in the near future, millions of lives will be improved, including those who may have been afflicted with AD, their families, and the pertinent members of the global socioeconomic system.

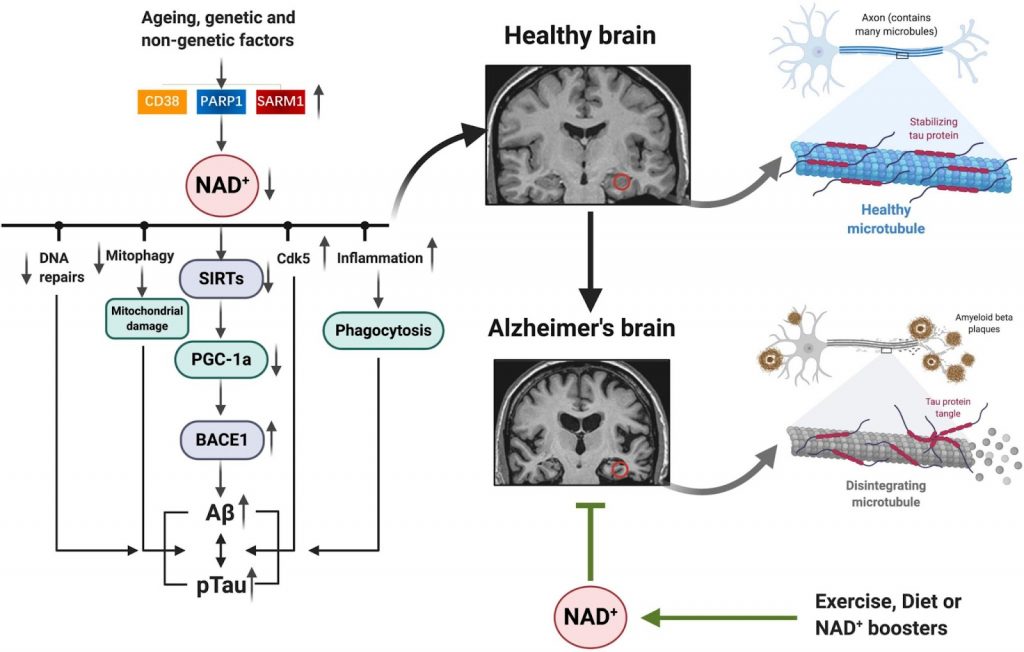

One possible treatment for AD could be boosting NAD+. NAD+ declines with aging and contributes to much of the cellular dysfunction that leads to AD. In several animal studies, boosting NAD+ has been shown to reduce AD pathology like the buildup of amyloid. Boosting NAD+ has also been shown to improve learning and memory. Thus, boosting NAD+ seems like a promising treatment for the prevention of AD.

(Wang et al., 2021 | Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology) Boosting NAD+ to Prevent Alzheimer’s Disease. With aging, the depletion of NAD+ leads to the dysfunction of cellular processes like DNA repair and mitochondrial clearance which leads to the buildup of AD-related proteins like amyloid. Boosting NAD+ could mitigate these cellular disruptions and prevent the buildup of toxic proteins, ultimately preventing AD.