Key Points:

- NR prevents weight gain in mice fed a high-fat diet.

- Fecal matter transplants from NR-treated mice also prevents weight gain.

- NADH — a form of NAD+ — is elevated in the fecal matter of NR-treated mice.

Obesity, common among Western and elderly populations alike, brings about age-related diseases like type 2 diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease. Since diet and exercise can be difficult for some folks, scientists have been trying to find new ways to alleviate the obesity epidemic. Now, investigators from the Medical College of Wisconsin have gathered data supporting the anti-obesity effects of nicotinamide riboside (NR).

In mSystems, Lozada-Fernandez and colleagues report that NR prevents weight gain in mice fed a high-fat diet, largely by altering gut bacteria composition. This was demonstrated by transferring fecal matter from NR-treated mice to untreated mice. The untreated mice given NR-conditioned fecal matter gained less weight in response to a high-fat diet, similar to NR-treated mice. This lack of weight gain is attributed to burning calories more efficiently and raising fecal matter NADH levels.

Fecal Matter From NR-Treated Mice Prevents Weight Gain

NR is known to reduce the weight gained from a high-fat diet in rodents. To confirm this, Lozada-Fernandez and colleagues fed mice a diet consisting of 60% fat (from lard). As expected, mice given NR (0.4%) in their drinking water gained less weight in response to the high-fat diet when compared to mice with no (0%) NR in their drinking water. NR-treated mice also exhibited changes in their gut bacteria — the bacteria that live within our digestive tract.

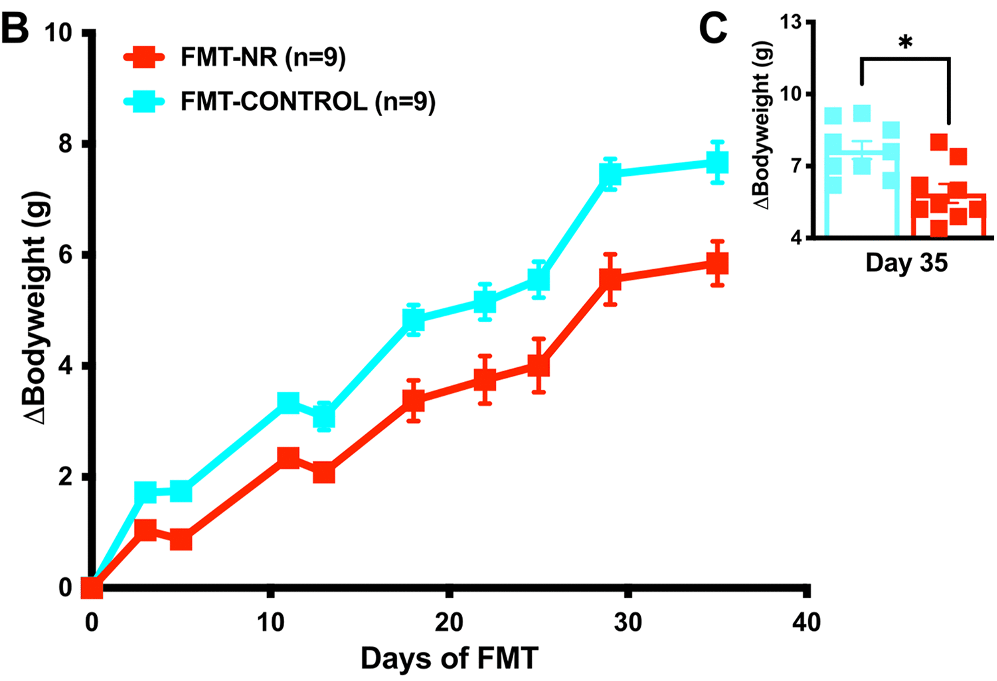

Our gut bacteria are intricately linked to our physiology and contribute to obesity. To determine if NR-induced changes in gut bacteria composition contribute to the alleviation of obesity, the Wisconsin researchers transferred the fecal matter from NR-treated mice fed 60% fat to untreated mice fed the same diet. The results were similar to NR-treatment itself, showing that NR-conditioned fecal matter prevents weight gain.

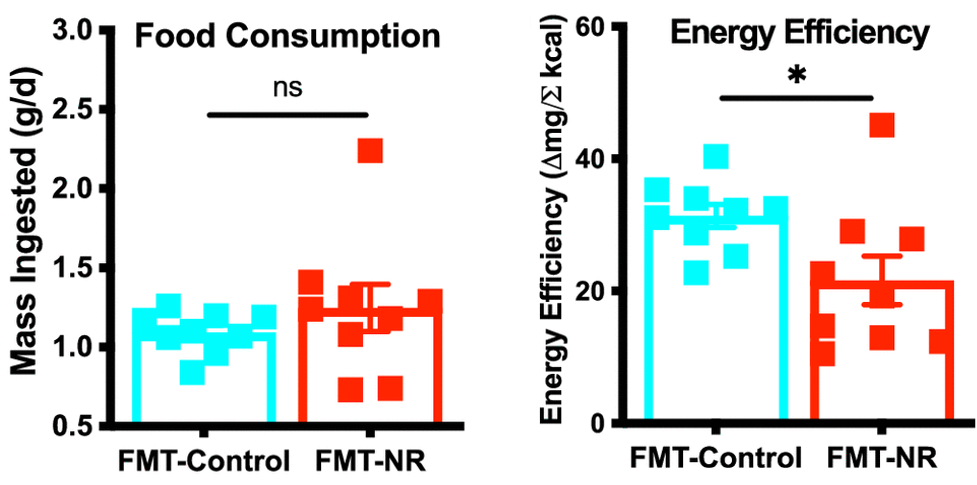

Lozada-Fernandez and colleagues next assessed the energy intake of mice given a fecal matter transplant (FMT) from NR-treated mice. There was no difference in food consumption or calories absorbed, but energy efficiency — the rate of weight gain per calorie absorbed — was reduced. It was concluded that mice given NR-conditioned FMT burn more calories than untreated mice, thus gaining less weight.

Lozada-Fernandez and colleagues found that NADH (the reduced form of NAD+) was elevated in the fecal matter of mice treated with NR. This suggests that NR could reduce weight gain by increasing gut bacteria synthesis of NADH. Still, it remains unclear how this works. It could be that NR-conditioned gut bacteria secrete molecules beneficial for weight loss when more NAD+ is available to them, or they could directly increase body-wide NAD+ levels.

Can Boosting NAD+ Treat Obesity?

The findings of Lozada-Fernandez and colleagues demonstrate once again that NR can reduce high-fat diet-induced weight gain. This was shown before in female mice in a study that also showed NR reduces fat mass. Additionally, supplementation with NR has been shown to decrease obesity-induced subfertility in mice. Similar to NR, another NAD+ precursor, nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) was shown to improve obesity-induced fertility problems. Boosting NAD+, whether by NR or NMN supplementation, may combat obesity by increasing fat cell metabolism.

While the animal studies mentioned above qualify NR as a potential anti-obesity agent, human NR studies have had limited positive results. However, at least one study has shown that NR can combat obesity. The study showed that NR reduced fat mass and increased lean mass in obese adults. The discrepancy between mice and human studies may be due to differences in mouse and human gut bacteria composition, which could alter how NR is metabolized, thus changing body-wide NAD+ availability.